|

Sax Therapy

.jpg)

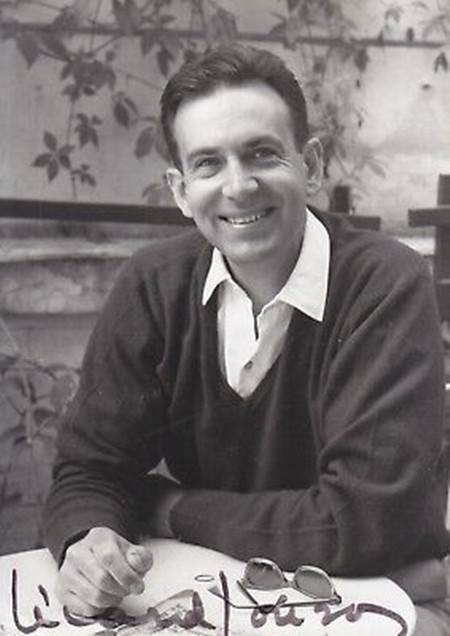

Yo Matsushita with his

soprano saxophone.

I’ve always had a soft spot for the saxophone, even

since I was a teenager. At the time, I was especially impressed with the

lyrical playing of Frank Trumbauer whose 1927 recording with Bix Beiderbecke

of Singing the Blues was considered a jazz classic. I once

laboriously wrote out the music by listening to the record over and over

again. Trumbauer was particularly associated with the C-melody saxophone

which had a lovely singing tone, though the instrument is rarely seen today.

In a way, it’s curious that the saxophone was so

eagerly employed by jazz musicians because it was invented in Belgium in the

1840s, long before the emergence of jazz. To be more accurate, a whole

family of saxophones was invented, ranging from the small soprano to the

elephantine bass. By the 1850s saxophones were often used in bands and small

ensembles all over Europe. The creator of this new instrument was the

Belgian inventor Adolphe Sax, who with touching modesty, named the

instruments after himself. Today only three types of saxophone are in common

use, the alto, tenor and baritone. The soprano sax, popularized by jazz

musician Sidney Bechet is less often encountered.

The saxophone was slow to enter the world of classical

music. Wagner evidently hated it, yet Berlioz, always on the hunt for

something new, was charmed by the instrument’s novel tone quality. Yet even

today it rarely appears as a member of the symphony orchestra. The French

saxophone player Marcel Mule was largely responsible for bringing the

saxophone into the classical world. He played in a restrained style using an

embouchure somewhat similar to that used for a clarinet which produced a

wonderful, fluid tone quality. His members of his eponymous saxophone

quartet played the same way and I remember being captivated when I first

heard their recordings. Debussy was probably the first major composer to

write a concert work for alto sax and orchestra in 1901, but the most

popular concerto is probably that by Glazunov, written in 1934. The 20th

century saw dozens of saxophone concertos appear, mostly for alto sax.

Paul Creston (1906-1985): Saxophone Concerto, Op 26. Rob Burton

(alto sax), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra cond. Mark Wigglesworth,

(Duration: 20:02; Video: 720p HD)

Paul Creston is one of the senior composers in American

classical music yet surprisingly he was self-taught. He was prolific too and

wrote six symphonies and a wealth of other compositions. Musically he is

rather conservative, yet the music has a rhythmic drive and melodic appeal.

This concerto dates from 1944 and it’s considered one of the composer’s

major works. Twenty years after its composition he re-scored for symphonic

band. The three-movement work requires advanced technique of the highest

order and this performance is especially rewarding because it’s given by the

20-year-old finalist of the BBC’s 2018 Young Musician competition, Rob

Burton. His playing is superb throughout, expressively phrased and

flawlessly articulated. The first energy-driven movement contrasts with the

lovely second movement (06:42) which is flowing and plaintive. The

scampering final movement (14:24) also bursts with energy yet has moments of

lyricism and reflection with a sudden, dramatic ending.

Narong Prangcharoen (b. 1973): Concerto for Saxophone - Maha Mantras.

Yo Matsushita (saxes), Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Dariusz

Mikulski, (Duration: 18:14; Video: 1080p HD)

This concerto is for both soprano and alto saxophones,

which are sometimes played simultaneously. The musical language is in sharp

contrast to the conservative style of Paul Creston. It stands firmly in the

21st century, sometimes with allusions to the folk and classical

music of Thailand. It’s powerful, compelling music by one of Thailand’s new

generation of composers who have achieved international success. Currently,

Dr. Narong serves as Dean of the College of Music,

Mahidol University

where he’s also the

composer-in-residence

for the

Thailand Philharmonic

Orchestra and the

Pacific Symphony

in

Orange County,

California. His compositions have won him the

Guggenheim Fellowship

and the

Alexander Zemlinsky

International Composition Competition Prize.

This technically challenging work is played by another

young musician of enormous talent. Yo Matsushita, who graduated at the Tokyo

University of Fine Arts provides a captivating performance and plays with a

rich and commanding tone quality with a keen sense of phrasing, dynamic

contrast and articulation.

This concerto was published in 2013 and its composer

writes, “Cast in one movement with many subplots, Maha Mantras is a

concerto for saxophonist switching between soprano and alto, and features a

dazzling tour-de-force cadenza in which the soloist plays both

instruments simultaneously… it’s based on pentatonic themes tinged with

highly ornate and chromatic shadings. The work’s title indicates a

magnification and development of the composer’s earlier work, Mantras

both compositions inspired by the creation of music as a healing force.”

Narong Prangcharoen’s concerto is powerfully charged

yet there are many moments of sublime calm. The middle of the work is an

extended cadenza which leads into a short final dramatic section with

pounding percussion, frenetic orchestral writing and the extreme top notes

of the soprano sax. It’s thrilling music.

|

|

Music at the Movies

Richard

Wagner.

Chatting with a friend over coffee recently, we were

reminding ourselves about famous movies that used classical music for their

sound tracks. Driving back home, I began to realize that a classical music

soundtrack is not such a novel idea as I first imagined. The concept goes

back to the earliest days of cinema. I read somewhere that music was

originally played during silent films not for any artistic purpose, but was

merely intended as a distraction from the continuous clatter of the

projector. It was usually provided by a pianist and many helpful books were

published to provide accompanists with suitable musical examples for various

scenes. It eventually became common practice for film distributors to

provide musical cue sheets with each print of the film. I would guess that

because many cinema pianists were classically trained, they would also draw

on their knowledge of the classical repertoire to supplement their partly

improvised performances.

The first days of January 1915 saw the premier of the

movie Birth of a Nation, hailed for its dramatic and visual

innovations. With a running time three hours it was longest film ever made

up to that point and its use of music was also something of a revolution.

But the film itself was silent because sound-on-film technology was not

developed until the mid 1920s. The composer and conductor Joseph Carl Breil

assembled a three-hour score for Birth of a Nation intended to be

played by an orchestra during the screening. He used adaptations of

classical works together with well-known melodies and newly composed music.

During the early years of sound film, classical music was used freely,

especially music from the nineteenth century.

But once the ability to synchronize

music and sound became possible, the role of background music started to

become an integral part of the movie and part of the story-telling process.

Thus began the role of the film music composer. Some of Hollywood’s most

influential film composers such as Max Steiner and

Erich Wolfgang

Korngold came from Austria or other parts of Eastern Europe and their

musical roots were deeply embedded in European romantic tradition. This is

indeed where the characteristic Hollywood Sound came from, with its

soaring melodies, rich orchestral textures and sumptuous harmonies.

Even so, some film directors were drawn to

classical music to underscore their films.

I suppose one obvious reason might have been that composers do not demand

fees or royalties when they have been dead for two hundred years. But

more importantly, classical music can add a sense if historical framework,

it can add a depth and breadth that is otherwise rarely achieved. Just think

back for a moment to some of the most compelling cinematic moments: the

opening scene of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey enriched by the

powerful music of Richard Strauss; the melancholy sequences in Visconti’s

Death in Venice which used music by Mahler and the brilliant use of

Wagner’s music in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now.

Richard Wagner (1813-1883): The Ride of the Valkyries. Berlin

Philharmonic cond. Daniel Barenboim (Duration: 05:05; Video: 720p)

It’s difficult to hear this piece without mental images

of helicopters surging towards the coast of Vietnam; such was the impact of

the music in Coppola’s movie, in which at first the music is barely audible

under the ominous drone of the helicopters then comes surging forward. The

music dates from the 1850s and is part of the opera Die Walküre (The

Valkyries) which is the second opera in the four that make up Wagner’s great

opera cycle, Der Ring des Niblungen. And case you’re wondering, a

Valkyrie is a female god-like being from Norse mythology who chooses those

who will die in a battle and those who will live.

The music gives the

spotlight to the brass instruments but in the original operatic version we

hear the battle cries of the Valkyries above the orchestra. The orchestral

version, without the shrieking Valkyries has become one of Wagner’s most

well-known works. Incidentally, I discovered this morning that this work

was also used in Joseph Carl Breil’s score for Birth of a Nation.

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943): Piano Concerto No 2.

Evgeny Igorevich Kissin

(pno),

Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France cond.

Myung-Whun Chung (Duration: 38:40; Video: 720p HD)

A few nights ago, I watched a cleaned-up print of David

Lean’s 1945 classic movie, Brief Encounter. After all those years it

is still a wonderful experience and in many ways a remarkable movie.

Throughout the film Lean draws on excerpts from Rachmaninov’s Second

Piano Concerto, one of the great piano works of the twentieth century,

though its heart is firmly in the nineteenth. As a teenager, I adored this

work and eventually saved up enough money to buy the Deutsche Grammophon

recording of the brilliant Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter playing it.

The dreamy and lyrical slow movement used to reduce me to a helpless

sniffling wreck. Sometimes, it still does.

|

|

Flute Fever

Two 18th

century ivory flutes and ivory piccolo.

If you are a bit hazy about which woodwind instrument

is which, you can’t really mistake the flute because in the orchestra it’s

the only woodwind instrument that is played sideways. The same goes for the

other members of the flute family which includes the piccolo (the Italian

name simply means “small”) and the larger and less often seen alto flute.

You might be surprised to know that there is even a contrabass flute, a

massive unwieldy contraption which is sometimes heard in flute ensembles. It

makes a strange and ghostly sound and gives some people the creeps.

Unlike other woodwind instruments which use a reed

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reed_(instrument) to produce the vibrating

air, the flute sound is created by blowing across the top of a hole at the

end (or head-joint) of the instrument in much the same way as children

produce an owl-like sound by blowing across the top of an empty bottle.

Flutes, in one form or another have been around for thousands of years. One

of the earliest examples was discovered recently in Germany: a simple

five-holed flute made from the wing bone of a vulture and shown to be 35,000

years old. Some other ancient flutes found in Europe are thought to be much

older, possibly 43,000 years. Of course, flute-type instruments are known in

different cultures all over the world and especially in Asia.

Traditionally, flutes were made of bone, bamboo or wood

but today, despite being classed as a woodwind instrument, most flutes are

made of metal. The exception is the piccolo which is usually still made of

wood. Student flutes are made of nickel, silver, or brass that has been

silver-plated, while many professional players prefer flutes made of solid

silver or gold. Some top professional players use instruments use flutes

made of platinum but they don’t come cheap. And for that matter, neither do

the players. Incidentally, in America, flute players are referred to as

“flutists” which seems logical, but in Britain they are known as

“flautists”.

During the Baroque, recorders were generally used in

ensembles but gradually they were replaced by flutes which had a brighter

and more penetrating tone quality. Even by the end of the 18th

century it was still a relatively simple instrument for the complex Boehm

system of mechanical key-work had yet to be invented.

W. A.

Mozart (1756-1791): Flute Concerto No. 1 in G Major, K.313. Yeojin

Han (flt), Korean Symphony Orchestra cond. Chiyong Jeong (Duration: 31:33;

Video: 720p HD)

Although Mozart evidently disliked the flute he wrote a

concerto for it, commissioned by the well-known Dutch flute player

Ferdinand De Jeann.

For generations, it was thought that Mozart wrote two flute concertos, but

in the 1950s evidence came to light that the second concerto was actually a

reworking of his own oboe concerto. The first concerto dates from 1778 and

its cast in the usual three movements. It receives a lively performance by

these fine Korean musicians and as a bonus the encore piece is Paganini’s

Caprice No 24, originally written for solo violin in 1807 and considered

by musicians to be one of the most difficult violin pieces ever written.

This work, you may notice is the one with the famous opening theme which was

since borrowed by dozens of other composers as a basis for orchestral

variations.

Carl Stamitz (1745-1801): Flute Concerto in G major.

Davide Baldo (flt), Bohčme Orchestra cond. Giuseppe Montesano (Duration:

17:56; Video: 1080p HD)

In the late eighteenth century, Mannheim had the finest

and most famous court orchestra anywhere. It attracted some of Europe’s best

instrumental players and composers and was lavishly funded by Duke Karl

Theodor. The composer Carl Stamitz is closely associated with the Mannheim

School and his father Johann is considered to be its founder. By the age of

seventeen Carl Stamitz was employed as a violinist in the Mannheim court

orchestra and his father must have had hopes for him. However, at the age of

twenty-five, Carl left his secure job in Mannheim and began concert tours

around Europe. For a time he lived in London. He was a prolific composer,

turning out more than fifty symphonies, sixty concertos and a large amount

of chamber music. The concertos are noted for melodic appeal and courtly

grace rather than virtuosity. Despite his musical achievements Stamitz was

less successful at managing his finances. He never managed to hold down a

job with one of the major royal courts. It seems that he taught at the

university at Jena, but received only a modest income. He began to sink into

debt and inevitably his funds ran dry. Then in January 1801, his wife died.

By the following November, Stamitz too was in his grave. All his

possessions, including many tracts on alchemy were auctioned to pay off his

debts. Whether Stamitz was studying alchemy to try and turn base metals into

gold, cure some disease or search for the elixir of youth we simply don’t

know.

|

|

Job for the Boyss

King’s

College, England.

If you do a search for “boy choir” on YouTube and trawl

through the countless videos that appear, you might be surprised to see the

vast number of boy choirs that exist. It might also surprise you, as it did

me, to see that huge numbers of them apparently exist to perform popular

music and little else. There are endless boy choir versions of pop songs,

folk songs, gospel songs, Christmas carols and music from shows and movies.

It seems that boy choirs are all the rage, especially

in America. Many of them are professionally trained; they have colourful

uniforms and an unmistakable commercial feel to the presentations. Far be it

from me to express cynicism, but perhaps there’s money to be made in the boy

choir business.

All this razzmatazz is a far cry from the traditional

concept of a boy choir, which in the quieter world of yesteryear was a

permanent feature of every cathedral and significant church. Choral music

developed during the early middle ages, largely due to the Christian church.

It thrived in the cultured atmosphere where learning, the arts, devotion to

duty and spiritual values were fundamental to life. In keeping with the

traditions of the early church, the singers were always men but boys were

needed to add a vocal contrast and also to increase the range of notes

available.

In the year 1498 the Emperor

Maximilian I

moved his court from Innsbruck to Vienna, some three hundred miles to the

north-east. He also instructed his court officials to employ a singing

master, two bass singers and six boys. This humble start became the

foundation of the Vienna Boys’ Choir, perhaps the most famous boys’ choir in

the world.

Boys’ choirs are usually made up of pre-pubescent boys

technically known as trebles or boy sopranos and whose voices

remain unbroken. Some boys have naturally lower voices and can sing in the

alto range while much older boys or men provide the tenor and bass parts.

Today, many European churches have permanent boy choirs

though since the end of the nineteenth century girls have also been included

in some choirs, much to the dismay of church music purists.

Nearly fifty cathedrals in Britain have permanent

choirs, most of them running both boy and girl choirs. A few cathedrals

still provide choral music on a daily basis, but this is an increasingly

rare phenomenon.

Giovanni Battista Martini (1706-1784):

Domine, Ad Adjuvandum Me Festina.

Georgia Boy Choir, cond.

David R. White (Duration:

07:02; Video: 1080p)

We

don’t hear much of Martini these days, though whether he has any connection

with the eponymous beverage is anyone’s guess. He was an amazingly prolific

composer and a well-known teacher who had his own private music school in

Bologna. Among his pupils was the young Mozart. Padre Martini was an

ordained priest and an avid collector of printed music. His personal library

was estimated to have contained a staggering 17,000 volumes and eventually

became the basis for the Bologna Civic Library.

This work is a setting of Psalm 69 and the title means

“Lord, My God, Assist Me Now.” It’s superbly performed by the Georgia Boy

Choir which, in case you’re

wondering, is from Georgia the state not Georgia the country. Unlike the

Vienna Boys Choir with its five hundred years of history, this choir is

relatively recent and was established in 2009 by its Artistic Director and

Conductor, David R. White. The choir has already acquired an international

reputation.

Gregorio Allegri (c. 1582-1652): Misereri Mei,

Deus. Choir of King’s College,

Cambridge cond. Stephen Cleobury (Duration: 05:43; Video: 1080p HD)

Not strictly a “boy choir”, this renowned choir from

England was established in 1449. Allegri started his musical life as a

chorister. He spent almost his entire life in the service of the church,

writing music especially for the Sistine Chapel in Rome. Today his most

well-known piece is the Miserere Mei, Deus (“Have mercy on me, God)

and the piece is shrouded in fascinating bits of history. For years it was

sung only during Holy Week at the Sistine Chapel and nowhere else. The

Vatican prevented copies of its music being made, so published versions of

the work did not exist. However, in 1770, the fourteen-year-old Mozart, who

was in Rome with his father, heard the work being performed at the Sistine

Chapel and later transcribed it from memory, thus creating the first

unauthorized copy. Or so the story goes. In more recent years, evidence has

gradually emerged that there might have been illicit copies in circulation

before Mozart’s visit.

The work was published in England in 1771 but the

version performed today contains a curious error that somehow crept into the

work. Because of an unexpected change of key which could have been the

mistake of a 19th century copyist, the work contains a top “C” in

the soprano part for which the Miserere has become well-known. In

this recording, you hear it first it at 01:43. Strangely, this top “C”, the

nightmare of many a boy soprano, didn’t appear in Allegri’s original.

|

|

Falling Rain

A small rain stick.

Yesterday I was pottering around among the books in the

study and among the bookshelves I suddenly came across an old rain-stick, a

curious thing which I bought at a Mexican festival on London’s South Bank

countless years ago. Perhaps you’ve not yet encountered a rain-stick. It’s a

cylindrical object, about thirty inches long and about three inches in

diameter and made from the trunk of a particular species of prickly cactus.

To make one, you cut out a section of the trunk, remove the spiky thorns and

then bash them back into the wood so that they protrude on the inside of the

tube. It’s slightly more complicated than this, because the thorns must be

arranged in a particular way. The whole thing is left out in the sun to dry

and later one end is sealed. Small pebbles or dried beans are poured inside

and the other end of the tube is sealed. When the tube is upended, the

contents trickle down catching on the thorns as they go.

The oddly satisfying sound is reminiscent of gently

falling rain, especially if you hold your ear close to the tube. It’s

thought that the rain-stick was invented by the Mapuche, the indigenous

inhabitants of present day Chile and Argentina. Similar devices are also

found in Asia and Africa where they’re more usually made of bamboo. The

Mapuche optimistically believed that sounding the rain-stick could bring

about a downfall though whether it actually worked is anyone’s guess.

Like other artifacts originally designed for everyday

use, they’re sometimes used as musical instruments, though in the concert

hall the sound is barely audible. One of the few orchestral works that

features a rain-stick is a thrilling concerto by one of Finland’s most

significant living composers.

Kalevi Aho (b. 1949): Sieidi - Concerto for Percussion and

Orchestra. Martin Grubinger (perc), Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra

cond. Gustavo Gimeno (Duration: 35:46; Video: 720p HD)

Kalevi Aho is a hugely productive composer and draws on

a wide range of musical genres to create his own soundscapes. He is known

especially for his large scale works which include seventeen symphonies,

thirty concertos, five operas and a great deal of chamber music. This

concerto dates from 2010 and uses a wide range of percussion instruments and

unusual playing techniques.

Watch out for the appearance of a vibraphone (at

14:30), a large xylophone-like instrument with aluminium bars and

motor-driven rotating disks at the top end of its resonator tubes, producing

a tremolo effect.

The concerto is performed by the Austrian percussionist

who provides a virtuosic display which is nothing short of thrilling. It’s

an incredible feat of musical memory too. Towards the end of the concerto

the thunderous sounds begin to die away and the work ends in almost total

silence with the sound of a rain-stick.

Joseph Schwantner (b. 1943): Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra.

Thomas Burritt (perc), Texas Festival Orchestra cond. Vladimir Kulenovic

(Duration: 30:56; Video: 1080p HD)

In many societies, the raw elemental power of drums,

bells and cymbals has ceremonial, sacred, or symbolic associations. The

first drum appeared after someone decided to place a dried animal hide over

a frame and then pull it tight so that it vibrated when struck. Perhaps it

was invented by accident. Percussion instruments were slow to enter the

developing orchestra of the eighteenth century but the timpani (or

kettle-drums) were the first, usually in the form of a pair of tuned drums

to reinforce the sound at climatic moments. The twentieth century saw the

rise of orchestral percussion as never before and composers frequently wrote

for a massive battery of instruments requiring a high level of skill to play

them.

Joseph Schwantner is a prolific American composer who

draws on many different musical traditions such as impressionism, jazz,

serialism, African drumming and minimalism. The Concerto for Percussion

dates from 1994 and was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic. The

soloist uses two groups of percussion, one placed behind the orchestra and

used during the first and third movements and another group placed in front

of the orchestra for the second. Not only that, but there’s also orchestral

percussion and timpani along with piano and harp. The work relies very much

on repetitive minimalist approaches with contrasting timbres and textures

and uses a wide variety of percussion instruments and playing techniques.

Oh, and if you’d like a rain-stick for your own

personal entertainment, you can buy them ready made at Amazon. They come in

a variety of styles and sizes and they’re pleasant things to have around the

home, especially the brightly decorated varieties. Alternatively, you can

hire my own rain-stick for a few days. There would, of course be a modest

fee.

|

|

The Harmony of Words

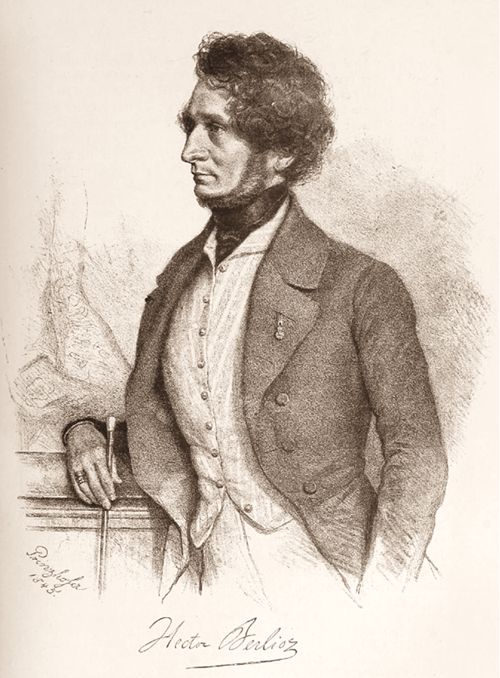

Hector

Berlioz in 1845.

A few months ago, during those distant

care-free days when we could wander the streets without surgical masks and

sit in a bar with a glass of half-decent wine, I overheard some bloke at a

nearby table remark loudly to his companion that he couldn’t stand poetry.

“A waste of words” he snorted and implied in his dismissive comments that

poetry was basically a load of arty-farty nonsense fit only for wimps and

fairies. Poor old sod! He had no idea what he’s been missing.

I resisted the temptation to comment

because I’ve found that if people tell you that they hate poetry, or hate

ballet or hate asparagus, further discussion is pointless. They will never

change their minds. Rather than become irritated with the poetry-hater, I

dismissed his fatuous remarks on the grounds that he is the loser. He will

never experience, let alone understand the joy of magical words.

Anyway, this all came to mind the other

day when I was looking through a book of poems by that remarkable Bengali

writer Rabindraneth Tagore. The book is entitled Gitanjali and inside

the front cover is my mother’s maiden name followed by the inscription

“Christmas 1934.” Looking through the yellowed pages and pouring over

Tagore’s mystical verses, I was strangely reminded of what the English

composer Henry Purcell wrote in 1650: “Musick and poetry have ever been

acknowledged sisters, which walking hand in hand support each other; as

poetry is the harmony of words, so musick that of notes…”

Music and poetry have indeed been

intertwined for thousands of years. Even the first lyric poets in ancient

Greece performed to the accompaniment of the lyre. From Elizabeth times

until the 19th century,

songs, music and poetry influenced each other in a kind of symbiotic,

reciprocal kind of way. The art songs of the great 19th century

song-writers were nearly always settings of existing poems. But even more

interesting was the 19th century

realization that poetry and literature could become the starting point for

music. Berlioz and Liszt spring to mind as two of the many composers who

turned to poetry. Richard Strauss drew heavily on German romantic poetry for

his massive, brooding orchestral works. There must be hundreds of classical

works that owe their existence to a poem. The English composers Gustav Holst

and Ralph Vaughan Williams often turned for inspiration to the poetry of the

American writer Walt Whitman.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): Toward the Unknown Region.

National Youth Orchestra and Choir of Great Britain cond. Vasily Petrenko

(Duration: 12:20; Video: 240p)

The evocative title of this work is

from a poem by Whitman, whose writing influenced many young artists and

musicians during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Vaughan

Williams was fascinated by Whitman’s poetry and the collection of poems

Leaves of Grass was a constant companion. The Sea Symphony of

1910, written for choir and orchestra uses Whitman’s poetry throughout.

Toward the Unknown Region was intended as a companion piece for the

symphony. It was actually finished before the symphony and first performed

at the Leeds Festival in October 1907 with the composer conducting. He

described it as a “song” for chorus and orchestra though it’s rarely

performed today. This is a shame, for it’s a wonderful setting of the poem

with superb choral writing, brilliant orchestration and soaring melodies.

This performance, recorded at The Proms in 2013 is fresh and captivating

with superb sound quality too. Try using a good quality headset to enjoy the

expansive spatial audio of the recording.

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869): Harold in Italy.

Antoine Tamestit (vla),

Frankfurt Radio Symphony cond. Eliahu Inbal (Duration: 43:56; Video: 1080p)

Many years ago my mother confided in me

that when she was a teenager, she loved to read the poetry of Lord Byron,

until she heard that he was “one of those horrid perverts.” In fairness to

Byron, I don’t suppose he was any more perverted than some of his other

artistic chums. However, if this revelation titivates your sensibilities, I

shall leave to explore the subject in your own time.

If you’re not familiar with this work,

you might find the title mildly puzzling. The eponymous Harold was a

character created by Byron and the subject of a lengthy, partly

autobiographical poem completed in 1818 and entitled Childe Harold’s

Pilgrimage. It describes the travels and reflections of Harold, a

somewhat world-weary young man who traipses around Europe looking for

distraction in foreign lands. The word “childe” is a medieval title for

someone who is a candidate for knighthood. Berlioz used Byron’s poem as a

basis for the music, which he described as “a symphony in four parts with

viola solo”. The viola reflects the character of Harold, the melancholy

dreamer. Berlioz was good at writing memorable tunes and the solo viola

enters with a remarkably beautiful melody (at 03:48) delicately accompanied

by strings and harp. Completed in 1834, it’s all splendidly romantic music

with a typically French lightness of touch. If Berlioz is new to you, here’s

a rewarding place to start.

|

|

Being Stubborn

Henry

Purcell.

Do you ever find that sometimes a

melody drifts into your mind without invitation? This happens to me quite

often and sometimes I don’t even recognise it. Recently I heard an orchestra

playing a short phrase in my mind. It was only two bars of six notes and I

could recall nothing else. After several days of musical agony, I wrote down

the phrase and emailed it to some musical friends. The next day, an email

arrived from a colleague who has a vast knowledge of the orchestral

repertoire. I was pretty sure he would know the answer - and he did. The

six-note phrase came from the Shostakovich orchestral suite, The Gadfly.

The last time I had heard the work was in Germany thirty years ago.

Last night, while making some coffee in

the kitchen I had a similar experience, but at least I knew the tune. You

probably know it too (if you’re old enough) because in 1963, it was a hit

for Shirley Bassey. The song was I who have nothing. I later

discovered that it was originally recorded in 1961 by the Italian singer Joe

Sentieri under the title Uno Dei Tanti. Now I have to admit that I am

not usually a pop music enthusiast, largely on the grounds that much of it

lacks musical interest. But this song has some interesting features.

It has a well-crafted tune in a minor

key which itself is unusual. As the intensity of the lyrics increase, the

pitch of the melody rises and the mood of despondency changes to one of

elation by suddenly switching into the major key. There are several moments

of dramatic silence in the song, yet one the most compelling features is not

so much the melody, but the persistent chugging rhythm of the accompaniment.

It creates a sense of urgency and helps to propel the music forward. This

repeated musical device is called an ostinato, a term derived from

the Italian word meaning “stubborn”. An ostinato can take the form a

melody or rhythm that repeats itself and becomes an integral part of the

music. In a few cases, notably Ravel’s Bolero, the ostinato

rhythm is repeated throughout the entire piece.

The notion of ostinato has been

around since medieval times and was used extensively during the late

renaissance and baroque. Sometimes the ostinato took the form of a melody in

the bass and became known as a ground bass or basso ostinato.

The English composer Henry Purcell was especially skilful at writing them

and his most famous one appears in the final aria of his one opera, Dido

and Aeneas.

Henry Purcell (1659-1695): Dido’s Lament, from “Dido & Aeneas”.

Malena Ernman, (sop), Choir and Orchestra of Les Arts Florisants con.

William Christie (Duration: 07:43; Video: 1080p HD)

This three-act opera was composed

around 1688. In this production, Dido the Queen of Carthage takes poison to

end her life. The final aria (“When I am laid in earth…”) begins with a

brief and typically chromatic introduction before the ground bass starts at

01:10, played on the cello. This haunting ostinato melody is repeated eleven

times throughout the aria. The music itself is loaded with baroque symbolism

and the chromatic ostinato descending melody suggests death and despair.

Purcell’s rich, sumptuous harmonies carry the soaring melody of the aria and

plaintive repeated phrase “Remember me!” is heart-breaking. The aria makes a

poignant conclusion to the opera and this powerful performance is probably

the finest you’re likely to encounter, both musically and dramatically. It’s

given by the Swedish soprano Malena Ernman who incidentally, is the mother

of the teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg.

Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706): Canon in D.

Ímpetus Madrid Baroque Ensemble, dir. Yago Mahugo (Duration: 04:30; Video:

1080p HD)

A canon is a piece of music in

which the melody is copied in turn by other voices or instruments. The type

of song known as a round is a simple canon. Think of the songs

Frčre Jacques and Three Blind Mice, in which voices sing the same

melody at different, though precise moments. In the hands of competent

composers, the canon could be made into an extended elaborate composition

with melodies weaving around each other. Pachelbel’s famous work cleverly

combines a three-part canon with a ground bass. In this performance, you’ll

hear the ground bass first; an eight-note phrase played on the cello and

later the double bass. It’s repeated 28 times throughout the piece. The

eight-note canon melody is heard on each of the three violins in turn before

the music gradually becomes more rhythmically complex. Composers found

canons fascinating, because the original melody could be modified and

elaborated in countless different ways. Just listen – this is exactly what

Pachelbel did.

|

|

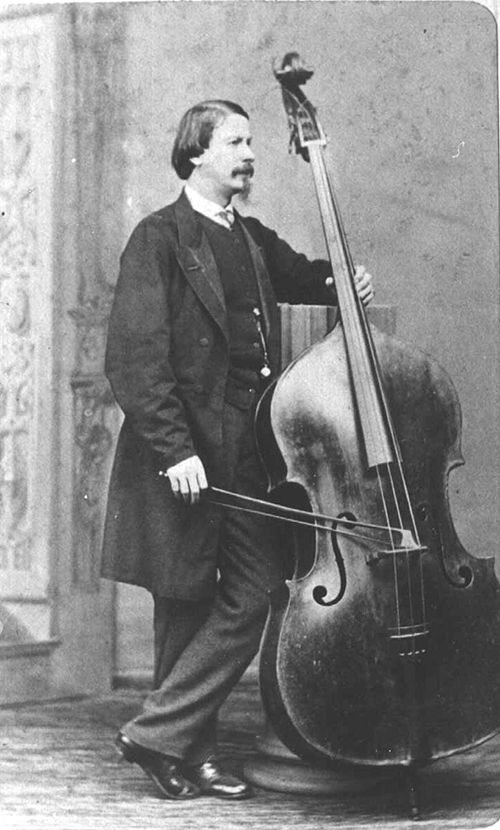

Down to Basics

Double bass

virtuoso Bottesini (c. 1865)

When I was a music student back in The

Old Country, I used to do some instrumental teaching to earn a bit of extra

money. Most of us students did some teaching, despite the fact we were

barely qualified. For a time, I taught cello at a school just outside

London. One day, the Head of Music asked me to teach some double bass

students presumably because the cello and bass looked vaguely similar. I

agreed, on the grounds that the students were beginners and more

importantly, I needed the money. Fortunately for me, they were also slow

learners.

Of all the bowed stringed instruments,

the double bass is the largest and most unwieldy. It is heavy, easily

damaged and impossible to fit into a normal car. From a distance, it looks

like a larger version of the other bowed strings. But appearances can be

deceptive. While the double bass is similar in construction to the violin,

it has some features of the older viol family. Bass strings are tuned in

fourths whereas all other orchestral strings are tuned in fifths so cello

and bass fingering for example, are completely different. Like the viol, the

“shoulders” of the body are sloping thus allowing the player to reach the

higher notes.

The modern double bass stands around

six feet from the top of the scroll to the end-pin which rests on the floor.

Players either stand, or sit on a high stool with the instrument leaning

against their body. Half-size and quarter-size basses are available for

young learners. The half-size bass is actually only about 15% smaller than a

full-size model.

If you are observant, you may have

noticed that not all bass players hold their bows the same way. This is

because there are two distinct types of bass bow. The “French” bow is

similar in shape and holding position to that of the violin and cello. The

older “German” bow is a different shape and held in a hack-saw position,

similar to that of a viol. There is considerable argument over which type of

bow is more efficient but it’s largely a matter of personal preference.

Another feature you might notice is an extra section of fingerboard mounted

at the top of the instrument. These extensions are quite common in British

and American orchestras and allow the player a few extra low notes.

In the past, few composers wrote

concerti for the double bass because of the technical problems. The main

difficulty is making sure that the bass is not overshadowed by the

orchestra’s volume. The low register doesn’t project well; so much of the

music has to be written in the more difficult high register. In addition,

few 19th century

bass players had an advanced technique.

Giovanni Bottesini (1821-1889): Concerto for Double Bass No. 2 in B minor.

John Keene (db), Sydney College of Music Chamber Orchestra (Duration: 15:49;

Video: 720p HD)

Giovanni Bottesini was born into a

musical family. As a teenager, he studied violin and probably would have

continued had not a curious opportunity arisen. Milan Conservatory was

currently offering two scholarships for double bass and bassoon and the

young Giovanni wanted a place. Within a matter of weeks, Giovanni switched

from violin to double bass and was good enough to be admitted to the

college. Within a few years he had become an exceptional player and began an

international career as “the Paganini of the Double Bass”. Not only did he

develop bass technique enormously, he also composed many works for the

instrument, some with challenging technical demands. His Concerto in B

minor dates from in 1845 and is now a standard work for the instrument.

You might be surprised to hear that the double bass can reach some

surprisingly high notes. These are known as “harmonics” and produced by

touching the string lightly at critical positions.

Serge Koussevitzky (1874-1951): Concerto for Double Bass Op. 3.

To-Yen Yu (db), Tainan National University of the Arts Symphony Orchestra

cond. Wen-Pin Chien (Duration: 17:04; Video: 480p HD)

Koussevitzky is remembered as an

orchestral conductor especially for his long stint with the Boston Symphony

Orchestra but it’s often forgotten that he began his musical career as a

bass player. At the age of fourteen he received a scholarship to attend

Music College in Moscow and was good enough to join the Bolshoi Theatre

Orchestra at the age of twenty.

This three-movement concerto dates from

1902 and the opening theme bears a remarkable resemblance to the main theme

of Dvorak’s New World Symphony. The similarity is so startling that

one wonders how Koussevitzky got away with it. Nevertheless, the work has

become the best-known piece for double bass by a Russian composer and

probably the most popular concerto in the bass literature.

|

|

Unwanted Serenades

Humperdinck

c.1894.

When I’m looking for a restaurant in an

unfamiliar place, I tend to avoid those that are completely empty. Another

reason to stay away is the ominous sight of a piano or other musical

instrument awaiting attention. You see, as far as I am concerned, background

music and especially “live” background music is usually nothing more than a

pointless distraction. Contrary to popular belief, objectors to background

music often outnumber those who feel they need it. Twenty years ago, Gatwick

Airport Management carried out a survey of customers’ attitudes to the piped

music then being played throughout the airport. Nearly half the respondents

claimed they wanted it to stop. And it did.

I like to visit Kuala Lumpur from time

to time. In the past I usually stayed at an old-fashioned budget hotel in

the city centre because it was cheap. The downside was that some of the

bedrooms had the charm of detention cells and the bathrooms were almost

medieval. The beds always seemed to be slightly damp and the lumpy pillows

felt as though they had been stuffed with dead hamsters.

One evening, to escape from these grim

surroundings I went to a familiar Italian restaurant. Peering through the

window, I could see that since my previous visit, a space among the tables

had been reserved for resident musicians. It contained the usual impedimenta

of their calling: an electronic keyboard, some spidery music stands, a pair

of bongo drums, a microphone and a battered loudspeaker. But I was hungry

and looking forward to an authentic lasagne, so this wasn’t going to put me

off. I ventured inside and requested a table as far from the instruments as

possible. Eventually two morose individuals traipsed in, one of them

clutching a guitar. He started to tune his instrument loudly, when suddenly

there was the satisfying twang of a breaking string, thus proving once again

that prayers are answered if you try hard enough.

By the time the guitarist had returned

with a replacement string, I was well into the lasagne and the Chianti had

induced a more tolerant frame of mind. So I thought today we might explore

some music that’s connected with food though I was surprised to discover

that few symphonic composers have found inspiration in what we eat.

Engelbert Humperdinck (1854-1921): Prelude, “Hänsel and Gretel”.

German Radio Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Christoph Poppen (Duration: 07:39;

Video: 1080p HD)

Humperdinck’s reputation today rests

almost entirely on his opera Hänsel and Gretel which he started in

1890. It was based loosely on a fairy tale about a young brother and sister

by the Brothers Grimm and originally took the form of a puppet show with

songs and piano accompaniment. Humperdinck must have seen the operatic

potential because in 1891 he started working on the full orchestral version.

Richard Strauss conducted the premiere two years later and it was an

enormous success. In 1923, it was chosen for the first-ever radio broadcast

of an entire opera from London’s Royal Opera House.

The music has a Wagnerian flavour as

well as memorable melodies and typically the Prelude which is an

overture in all but name, is a mélange of the melodies in the opera. You

might recall that the opera features a gingerbread house with a roof made of

cakes, licorice windows and walls decorated with biscuits. The plot also

includes references to strawberries, rains almond and gingerbread children.

Far too many calories if you ask me, but there are plenty of good tunes.

Bohuslav Martinu (1890-1959): La Revue de Cuisine.

Cologne Chamber Soloists (Duration: 15:24; Video: 1080p HD)

Martinu composed six symphonies,

fifteen operas, fourteen ballet scores and a staggering quantity of other

works. He wrote La Revue de Cuisine in 1927 and it was his first

major success. It was originally a jazz ballet in which the dancers played

the roles of cooking utensils which surrealistically swagger through

romantic episodes of kitchen life. The suite that Martinu later assembled

from the ballet music is scored for clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, violin,

cello and piano. It has four movements: Prologue, Tango, Charleston,

and Final. However, this jazz-inspired music is by no means typical

of the composer’s style for much of his work is focused on loftier thoughts.

Although La Revue de Cuisine is

full of catchy melodies and evokes the popular music of the day, it also

uses complex rhythms and many irregular time-changes. The neo-classical

Prologue leads to a sombre, dreamy tango with a solo from the muted

trumpet and a lovely lyrical passage for bassoon and clarinet, accompanied

by pizzicato strings. It leads without a break into the jubilant

Charleston which brilliantly captures the spirit of that once-popular

dance. The deceptively simple Final shows Martinu’s prolific melodic

invention and skillful instrumentation. But perhaps more importantly, it’s a

tremendous bit of fun.

|

|

Country Folk

Composer

Gustav Holst.

Some years ago, I happened to be driving along the

North Shore of Switzerland’s Lake Geneva, en route to somewhere else, though

I have forgotten exactly where. In Lausanne that morning, I’d bought an

audio cassette of traditional Swiss folk songs. Later, my companion shoved

the cassette into the car’s player and the first track turned out to be a

yearning folksong from some Swiss mountain village. The lyrical music added

a magical dimension to the alpine scene before us. Now, if you’re familiar

with that part of the world, you’ll know that the scenery is pretty stunning

anyway, but the evocative music we were hearing belonged to the

landscape and somehow enriched the experience.

I’ve always been fascinated by folk music, partly

because it so often encaptures the spirit of a country or region. The folk

songs of Britain spring to mind. Despite the relative smallness of the

country, the diversity of British folk music is extraordinary. Folk songs

can often be traced far back into antiquity and in those bygone days, when

people were working, threshing or pulling loads of timber, singing was a

common activity. Not only did the songs reduce the boredom of repetitive

tasks, they also set the pace for synchronized activities that involved

teams of workers. Many sea shanties served exactly this purpose. During

leisure time, telling stories and singing the old songs were popular forms

of self-made entertainment.

Folk music has been defined as music that has evolved

by a process of oral transmission over a period of time. The word

folklore was coined as recently as 1846 by the English antiquarian

William Thoms who described it rather pompously as “the traditions, customs,

and superstitions of the uncultured classes”.

In Europe, the concept of nationalism was firmly

established by the 19th century when it became one of the most significant

political and social forces in history. Encouraged by waves of nationalist

fervour, many composers took a renewed interest in their country’s folk

music. In England, Cecil Sharp listened to hundreds of village folk singers

and painstakingly wrote down their songs. Zoltán Kodaly and Béla Bartók did

much the same in Hungary. Many European composers sought to develop a

musical style that somehow reflected the essence of their homeland. To

achieve this they inevitably turned to folk music.

Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904): Four Slavonic Dances.

Gimnazija Kranj Symphony

Orchestra (Slovenia) cond.

Nejc Becan

(Duration: 18:57; Video: 1080p HD)

The Slavonic Dances were inspired by the

Hungarian Dances

of

Johannes Brahms,

a set of twenty-one lively dances composed for piano in 1879. Dvorak’s

publisher knew that the Brahms pieces were selling well and suggested that

Dvorak might write something along similar lines. Originally for piano duet,

the sixteen dances were published in two sets, the first in 1878 and the

second in 1886. Whereas Brahms used original Hungarian melodies, Dvorak took

typical Slavonic dances as models but used melodies that were entirely his

own. His publisher was impressed, and requested Dvorak make orchestral

arrangements. They have since become some of the composer’s best-loved

music. Performances of the two complete sets are rare and conductors tend to

pick and mix to suit the programme time available.

This colourful performance features the orchestra of

Kranj Secondary School in Slovenia. The school was founded over two hundred

years ago and the enormous orchestra uses a modern arrangement which

includes four saxophones, two guitars and accordion, none of which appeared

in Dvorak’s original score. Purists might foam at the mouth at these

additions to the composer’s already superb orchestration but it doesn’t

worry me too much under the circumstances. It was after all, the school’s

“Great Christmas Concert” and for such events, certain liberties can be

tolerated. I enjoyed the orchestra’s enthusiastic performance along with the

sheer exuberance and joie de vivre.

Gustav Holst (1874-1934): St Paul's Suite.

Eufonico String Orchestra

in Zdunska Wola, Poland cond. Rafal Nicze (Duration: 14:56;

Video: 1080p HD)

Here’s another compelling high school orchestra

offering, this one from Poland. You’d be forgiven for assuming that the

title of this work refers to the Biblical St Paul, but it takes its name

from St Paul’s School for Girls in Hammersmith, West London. Despite his

foreign-sounding name, Gustav Holst was English and he served as the music

teacher at the school from 1905 to 1934. This ever-popular work was

published in 1922 and it’s one of many he composed for the school’s

orchestra. The lively music draws its inspiration from folk song and dance

and it’s easily approachable too, full of rich modal melodies and

quintessentially English in spirit. If you don’t know the work, you might

get a surprise (at 11:23) during the last movement when the melody of the

most well-known of all English folksongs creeps into the rich texture of

sound.

|

|

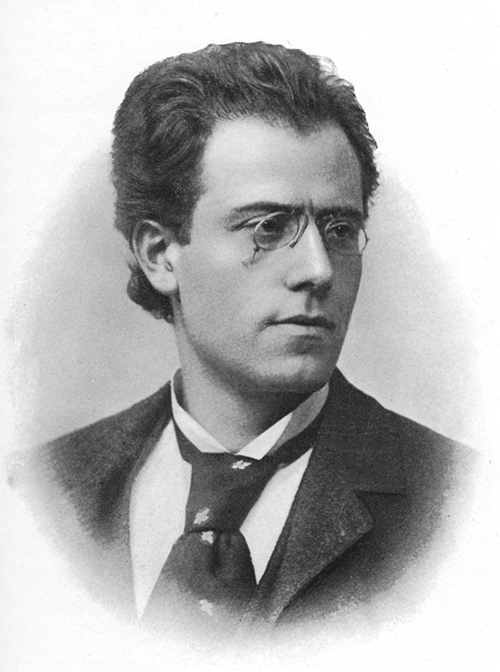

Big Ideas

Gustav Mahler.

Strangely enough, the word “orchestra”

originally meant a place, not a thing. In ancient Greece, the orchestra

was the circular space used by the chorus in front of the proscenium. It was

not until the 17th century

that the word assumed its modern meaning. The orchestra we know today has

its roots in the groups of instrumental players who were employed by royal

or noble families or those who could afford to employ resident musicians.

Mind you, they weren’t paid very much but usually a good deal more that what

churches offered, which was another source of employment for musicians.

Before 1750 the standardized orchestra

was unknown. Ensembles at royal households were pretty small and consisted

of whatever musicians were available, though stringed instruments

predominated. Part of the reason was economics because the larger the

ensemble, the more people you had to pay. In any case, musical performances

were informal private affairs held in room a within a royal household. It

wasn’t until the appearance of public concerts that larger orchestras became

necessary.

In France, the first public concerts

were called Concerts Spirituels because they were held on religious

festival days when other forms of entertainment were closed. They flourished

in Paris throughout the 18th century

and the idea was taken up in other countries. Public concerts involved

larger audiences and to meet the need for greater volume, orchestras began

to expand in size. The string section remained the foundation while other

instruments were added if and when they were needed. Most symphonies of the

period for example, were scored for strings with just a couple of oboes and

horns.

It was not until the early years of the

19th century

that the full woodwind and brass sections began to appear. Part of the

reason was that the development of music schools and colleges meant that

more skilled instrumental players were available. By the end of the 19th century,

orchestras sometimes consisted of sixty or seventy players. Some composers

wanted even bigger orchestras to produce the sheer volume and expansive

sounds that they needed.

Mahler scored his eighth symphony for a

massive orchestra and choir, which is why it has acquired the nickname

Symphony of a Thousand. And in case you’re wondering, the world’s

largest orchestra was assembled in Australia in 2013 to achieve a new

Guinness World Record. It consisted of seven thousand participants ranging

from beginners to professional musicians. The gargantuan ensemble played a

medley which included Waltzing Matilda and Ode to Joy. It’s

all good fun but I don’t suppose you would want to hear it very often.

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911): Symphony No. 5.

Lucerne Festival Orchestra, cond. Claudio Abbado (Duration: 01:13:42; Video:

720p HD)

Well, can anything new be said about

Mahler symphonies in a few words? I doubt it, but Mahler’s massive ten

symphonies cover almost every aspect of human expression. They also form a

cultural bridge between the German musical traditions of the nineteen

century and those of the twentieth. After several decades of neglect, the

1950s saw Mahler’s work and especially his symphonies being rediscovered by

a new generation of listeners. Mahler has become one of the most frequently

performed and recorded of all composers. He completed this much-loved

symphony in 1902. It’s a powerful, emotional work for a large orchestra and

you’ll need to put an hour aside to hear it. If this seems a bit daunting,

try taking it in smaller chunks – a movement at a time. I’m sure Mahler

wouldn’t mind. The third movement (45:10) is best known from its use in the

1971 Visconti movie, Death in Venice.

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869): Grand Messe de Morts.

WDR Choir, WDR Symphony Orchestra, cond. Jukka-Pekka

Saraste (Duration: 01:19:58; Video: 720p HD)

The French composer Hector Berlioz was

the son of a provincial doctor and attended medical school in Paris, before

defying his family’s wishes and taking up music as a profession. His

independent spirit and dismissal of tradition caused put him at odds with

the conservative musical establishment of Paris. But presumably not the

French government, which commissioned this Requiem, completed in 1837.

Berlioz scored his Grande Messe des

Morts for over four hundred musicians: over 200 in the orchestra and

another 200 choral singers. Berlioz evidently remarked that if there had

been enough space, he would have preferred 800 hundred voices. It seems he

was never satisfied. The orchestra includes four off-stage brass ensembles

and sixteen timpani, though the performance in this video, recorded in

Cologne’s impressive cathedral is somewhat scaled down. To my mind, the

sound is more well-defined as a result. If you haven’t got an entire hour to

spare, just listen to magnificent Tuba Mirum (“Hark the trumpet”) at

15:00 to get a sample of this fine work.

|

|

Licorice Sticks

The complex

mechanism on a modern clarinet (Photo: Bob McEvoy).

“To what?” I suppose you could

justifiably enquire. The expression is old jazz slang for a clarinet because

of course, clarinets are usually black. I’ve sometimes heard orchestral

players use the term but only when they’re joking, drunk or both. When I was

a music student in London, I used to share a flat with a clarinetist. Unlike

me, he was an extremely diligent student and practised his clarinet for

hours every day. When he wasn’t practising he was sorting out reeds with

which he seemed obsessed. He used to buy Vandoren clarinet reeds in Paris,

returning with several boxes which would then be carefully sorted and

graded. This was followed by more hours of practising. All this endless

labour paid off because he eventually became a world-class professional

musician.

Although the clarinet has a permanent

place in the modern orchestra, it wasn’t always thus. And it wasn’t always

black, either. The instrument first appeared during the early years of the

eighteenth century and it was a clever development of a simple reed

instrument called the chalumeau (SHA-loo-moh). The word is still used

today to describe the low register of the clarinet. It looked a bit like a

wooden tenor recorder to which someone had stuck a few brass levers here and

there. By the late eighteenth century more keywork had been added to make

the instrument capable of playing more technically demanding music. Usually

made of boxwood, these early clarinets were light brown and didn’t acquire

the licorice colour (and the complex modern mechanism) until many years

later.

The “standard” clarinet is actually

part of a much larger family of clarinets some of which are now so rare that

they’re encountered only in museums. Nowadays, you can sometimes spot the

small E flat clarinet and the bass clarinet in orchestras. The enormous

contrabass clarinet rarely makes an appearance. It’s an odd-looking

contraption and looks more like a science-fiction military weapon that a

musical instrument.

Johann Stamitz (1717-1757): Clarinet Concerto in B flat Major.

Jaehee Choi (clt), NFA Project Orchestra cond. Charles Neidich (Duration:

16:55; Video: 720p HD)

Johann Stamitz was one of the most

prolific and important composers of the mid-eighteenth century. He wrote

nearly sixty symphonies and invented, if that’s the right word, the

four-movement symphony which remained a standard format for years to come.

In the early 1740s he was appointed as Musical Director to the Elector

Palatine whose court was at Mannheim. Stamitz was in charge of the court

orchestra and he developed various orchestral techniques (including the

rapid ascending figure known as the Mannheim Rocket) and brought the

well-disciplined orchestra considerable fame. It was once described by Dr

Charles Burney as “an army of generals”. Years later, Mozart heard this

orchestra and was especially impressed by the clarinets.

It was once thought that this work of

1755 was the first clarinet concerto ever but modern research has shown this

is not the case. The Stamitz concerto is played here on a modern instrument

and it’s typical of the court music of the period, exhibiting the

much-valued classical ideals of dignity, poise and elegant melodies;

qualities from which Mozart would later take inspiration.

Aaron Copland (1900-1990): Concerto for Clarinet and String Orchestra.

Martin Fröst (clt), Norwegian Chamber Orchestra (Duration: 15:35; Video:

720p HD)

Few composers have the gift of writing

music that sounds truly American but Copland is one of them. You can almost

sense the vision of a vast prairie with distant hills; a pastoral landscape

bathed in radiant early-morning sunshine. Copland started the work in 1947

and scored it for strings, piano and harp. It was commissioned by jazz

clarinetist Benny Goodman who evidently paid two thousand dollars for the

work, a considerable sum in those days. There are just two movements, linked

by a cadenza – a standard part of most concertos and usually intended

to display the soloist’s technical skills. The first movement is slow and

expressive, full of what’s been described as Copland’s “bitter-sweet

lyricism”. The cadenza introduces some of the Latin-American and jazz themes

that dominate the lively second movement.

This is one of the best recordings

around: not only a brilliant soloist but an incredibly good chamber

ensemble. Just listen to the sparkling and virtuosic coda section from 14:15

onwards and the thrilling glissando on the last chord! As a teenager, I used

to have a treasured LP of this work featuring Benny Goodman himself. But the

playing was urbane and over-polite, as though Goodman was attempting to

shake off his jazz persona and sound like a “classical” musician. This

stunning Norwegian performance is much more exuberant and leaves the old

Goodman recording rather in the shadows. Sorry, Benny.

|

|

Japanese Delights

Composer Yuzo Toyama.

Let’s start with a Quiz Question, so

please sit up and look as though you’re interested, especially those people

shuffling around at the back. Now then, can you give me the names of three

20th century

Japanese composers? This is not too difficult because if you cast your eyes

down the column you will see that I have generously given you two names

already, but what about a third? Let me try to jog your memory. You might

recall the name of Toru Takemitsu who is perhaps the most revered among 20th century

Japanese composers. He composed hundreds of works that combine elements of

Eastern and Western music and philosophy, to create his own unique sound

landscape. More than anyone, Takemitsu put Japanese music on the map.

Since the latter half of the nineteenth

century, Japanese composers have tended to look towards Western musical

culture as well as drawing on elements from their own traditional music.

Komei Abe was one of the leading Japanese composers of the twentieth century

and his First Symphony of 1957 is a good introduction to Japanese

classical-music-in-the-Western-style although it’s a curious mix of musical

idioms. The prolific Toshiro Mayuzumi composed more than a hundred film

scores and if you’d like an entertaining musical experience, seek out his

Concertino for Xylophone and Orchestra. Kunihico Hashimoto was another

leading Japanese composer whose music reflects elements of late romanticism

and impressionism, as well as of the traditional music of Japan. The strange

thing is that Japanese orchestral music simply doesn’t seem to have caught

on in the West. There’s no obvious reason why this is the case. At least, I

cannot think of one.

Yuzo Toyama (b. 1931): Rhapsody for Orchestra.

Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Eiji Oue (Duration: 09:54; Video: 1080p

HD)

Yuzo Toyama is a native of Tokyo who

studied with Kan-ichi Shimofusa, a pupil of the German composer Paul

Hindemith. The Rhapsody for Orchestra is probably the composer’s

best-known work. He is also known as a conductor and for years held the post

of chief conductor with the NHK Symphony Orchestra. In case you are

wondering, NHK stands for Nippon Hoso Kyokai - the Japan Broadcasting

Corporation. In 1960 Toyama conducted the orchestra on a world tour on which

the orchestra performed several of his most popular works. His most

important musical influences were probably Bartók and Shostakovich and he is

fond of incorporating Japanese traditional music into his work, drawing on

folksongs and the classical Japanese dance-dramas of Kabuki theatre. Toyama

has written well over two hundred compositions and has received numerous

awards in Japan for his contributions to the nation’s musical life. The

Rhapsody for Orchestra dates from 1960 and it’s is based on Japanese

folk songs in which traditional instruments, including the kyoshigi

(paired percussive wooden sticks) are blended into a conventional Western

orchestra. You’ll notice distinctive Mikado-like moments from time to

time. The work starts with thunderous percussion so don’t set the volume

control too high. With excellent sound and video, the performance looks

superb in full screen mode.

Takashi Yoshimatsu (b. 1953): Cyberbird Concerto, Op. 59.

Hiromi Hara (sax), Shinpei Ooka (pno), Shohei Tachibana (perc), Shobi

Symphony Orchestra cond. Kon Suzuki (Duration: 26:21; Video: 1080p HD)

Yoshimatsu is also from Tokyo and like

his compatriot Toru Takemitsu, didn’t receive formal musical training until

adulthood. He left the faculty of technology of Keio University in 1972 and

became interested in jazz and progressive rock music, particularly through

electronic means. Yoshimatsu first dabbled in serial music but eventually

became disenchanted with it and instead began to compose in a free

neo-romantic style with strong influences from jazz, rock and Japanese

traditional music. He’s already completed six symphonies, twelve concertos,

a number of sonatas and shorter pieces for various ensembles. In contrast to

his earlier compositions, much of his more recent work uses relatively

simple harmonic structures.

This curiously-named work is

technically a triple concerto and the ornithological reference reappears in

his Symphony No. 6 written in 2014, subtitled Birds and Angels.

Yoshimatsu described this concerto as alluding to “an imaginary bird in the

realm of electronic cyberspace.” It’s a concerto for saxophone in all but

name and uses a free atonal jazz idiom for the soloists against a

conventional symphony orchestra. It was composed in 1993 for Hiromi Hara who

performs it on this video. The three movements are entitled Bird in

Colours, Bird in Grief, and Bird in the Wind. There’s some

brilliant playing from these talented young musicians with a lovely haunting

second movement and a joyous third movement with some fine brass writing and

a thunderous ending. If you are into eclectic modern jazz this video, with

its superb sound and video, will be right up your soi. As Mr Spock in

Star Trek might have said to Captain Kirk, “It’s classical music Jim,

but not as we know it.”

|

|

Just a Song at Twilight

Composer

James Molloy (1837-1909)

You can probably sing that famous line

even though the song was written before you were born - and probably before

your parents were born. The song has an interesting tale behind it. For a

start, the words were not written at twilight but at four o’clock in the

morning. The insomniac writer was one Graham Clifton Bingham, the son of a

Bristol bookseller. He was a prolific writer with 1,650 song lyrics to his

name. Just a song at Twilight is the opening line of the chorus to a

song called Love’s Old Sweet Song which was published in 1884 with

music by the Irish composer James Lynam Molloy. Some of Molloy’s music

became so popular in the early 20th century that it gained almost folksong

status. He wrote still-famous Kerry Dance in 1879.

Love’s Old Sweet Song

was extremely popular during the 1890s when the Gilbert and Sullivan operas

were all the rage, especially in London. In 1898 The Gondoliers was

premiered at the Savoy Theatre, running for over five hundred performances.

It includes a song entitled When a Merry Maiden Marries and the

opening bars bear more than a striking resemblance to Love’s Old Sweet

Song. When Sir Arthur Sullivan was accused of stealing part of James

Molloy’s melody, he denied it with the famous response, “We had only eight

notes between us”.

Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924): Coro a boca cerrada

(Humming Chorus).

Schola Cantorum Labronica, Lucca Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Andrea

Colombini (Duration: 03:18; Video: 720p HD)

Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly

has an even more interesting background. The story is somewhat convoluted

and I shall try to keep it short. So please sit up straight and try and look

as though you’re interested. In 1887 a semi-autobiographical French novel

appeared, entitled Madame Chrysanthčme written by Pierre Loti, the

pseudonym of Louis Marie-Julien Viaud who was a French naval officer and

novelist, known for his stories set in exotic places. The novel told the

story of a naval officer who was temporarily married to a Japanese girl

while he was stationed in Nagasaki. The plot was based on the true-life

diaries kept by the author. The novel came to the attention of the French

composer André Messager who used it as the basis for an opera of the same

name, first performed in Paris in 1893.

Meanwhile across the Atlantic, an

American lawyer and writer named John Luther Long published a short story

entitled Madame Butterfly. It was also based partly on the Pierre

Loti novel and on the recollections of his sister who had been to Japan with

her husband. The American playwright and theatre producer David Belasco

adapted Long’s story as a one-act play entitled Madame Butterfly: A

Tragedy of Japan. After its first run in New York in 1900 the play moved

to London where by chance was seen by the Italian composer Puccini who

decided that it would make a good opera and arranged for an Italian libretto

to be written. Four years later, Puccini’s Madama Butterfly was

premiered at La Scala in Milan. Unfortunately, it was not

particularly successful, largely due to inadequate rehearsal time. The

composer revised the work five times and his final version of 1907 is the

one that’s performed today. It has become one of the world’s most popular

operas: the tragic love affair and marriage of a naive young Japanese girl

to a thoughtless and callous American playboy Naval Officer.

The Humming Chorus is a

wordless, melancholy tune heard from off-stage at the end of Act 2 when the

Japanese girl Cio-Cio-San (Butterfly), her child and her servant Suzuki are

waiting at home one evening for the return of the American husband whose

ship has just in the harbour. They are unaware of the devastating news and

subsequent tragedy that is about to unfold.

Frederick Delius (1862-1934): Summer Night on the River.

Orquestra Clássica do Centro (Portugal) cond. David Wyn Lloyd (Duration:

06:37; Video: 1080p HD)

Delius is one of those composers whose

musical language you can usually recognise within seconds. In 1911 he

composed two short tone-poems for chamber orchestra, the first one being his

more well-known On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring. The two

pieces were written at the Delius house in the French village of Grez, near

Fontainebleau. The garden faced the small River Loing where Delius spent

many hours in contemplation. This river was the inspiration for the lilting

music of Summer Night on the River. Delius was gifted at creating a

sense of atmosphere in his music and in this piece the vague, water-colour

harmonies create an impressionistic picture of evening mists settling over

the river. You can almost feel the shifting waters, the gentle rocking of

small boats, the darkening of the skies and the deepening of the colours.

|

|

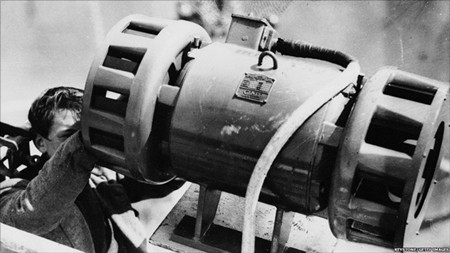

Minor Thirds

WW2 British air-raid siren.

A long time ago, when I was two or

three years old, we lived in an English village not far from the town of

Crewe. Every few days, I remember hearing dull, booming thuds which my

mother assured me were caused by trucks bumping along the road outside. This

seemed a bit unlikely as we rarely saw any trucks in the village. The noise

was in fact coming from German bombs exploding in the distance. Crewe was

known for its large railway junction and its enormous railway engineering

facility for manufacturing and overhauling locomotives. During World War II,

military tanks were also built there, so the town naturally became a

favourite target for the German Luftwaffe. The air raids were preceded and

followed by the distinctive wailing sound of air-raid sirens which were

installed in almost every town and village in the country. Sadly, for many

people the air-raid siren was one of the last sounds they heard.

At that tender age, I used to tinkle

around on my grandmother’s piano. My earliest musical memory was the

discovery that the notes B flat and D flat played simultaneously sounded

almost exactly the same pitches as the wailing air-raid sirens. I was

tremendously excited about this revelation though no one else shared my

enthusiasm. Perhaps they were more concerned about the bombs. Years later, I

discovered that the notes B flat and D flat create a musical interval called

a minor third. You might be wondering what it sounds like, especially if you

can’t tell a B flat from a wombat’s armpit. Think of the song

Greensleeves and sing the first two notes. Or sing the first two notes

of the Beatles song Hey Jude. Then imagine those two notes sounding

together. That’s a minor third, assuming that you’re singing in tune.

The distinctive sound of the minor

third helps to create the character of music in minor keys. Some people

describe the minor key as dark-sounding, soulful or heart-rending. Many folk

songs in minor keys tend to stay in the minor throughout, but if a symphony

is described as being in a minor key, you can be sure that it will drift

into a bright and sunny major key sooner or later. Strangely enough, during

the late eighteenth century, composers tended to avoid minor keys. Only two

of Mozart’s forty-one symphonies are in a minor key and Haydn, who wrote

over a hundred symphonies, chose minor keys for only seven. Only two of

Beethoven’s nine symphonies are in a minor key. This might be a reflection

of contemporary Viennese public taste because as the Romantic Movement

surged across Europe during the 19th century,

more symphonies appeared in minor keys. But let’s explore two less

well-known symphonies, both in minor keys and both equally rewarding.

Charles Ives (1874-1954): Symphony No. 1 in D minor.

The Perm Opera & Ballet Theatre Orchestra, Russia cond. Valeriy Platonov

(Duration: 38:39; Video: 720p HD)

Considered the grandfather of American

music, Charles Ives was born in Danbury, Connecticut. This attractive work

is the first of four symphonies and was composed between 1898 and 1902. It’s

written in a late romantic European style and the second movement is