|

|

|

|

Wine World

by Colin Kaye |

|

|

|

Persistent Myth

Few wines are made for ageing.

Some time ago, I was having dinner

at one of my favourite restaurants (now sadly gone) and I noticed someone at

a nearby table ordering a bottle of wine. My ears instinctively switched

into bionic mode and I realized that he was ordering a fairly ordinary but

reliable French wine, often seen in these parts. A few minutes later, the

waitress appeared, opened the bottle and poured a sample. This was airily

dismissed with something like, “Oh, I know this wine; I don’t need to taste

it.” Of course, the man had missed the point entirely. He wasn’t being given

a sample to see if he liked it because by ordering the wine, he had already

bought it. The sample is to check that the wine has not been damaged or

“gone off” in some way. It’s merely a quality check. In any case, tasting is

not strictly necessary. With experience, a few quick sniffs reveal whether

the wine is acceptable.

There’s a raft-load of other

misconceptions and wine myths that have been around far too long. Here are

six of them in no particular order.

Myth No 1: Leave the opened bottle of wine

to stand before serving.

This is a common belief held by

waiters who have presumably been instructed by the management to let the

bottle stand for a few minutes on the table “to let the air in”. This is

nonsense, because the air can reach only a tiny surface area of the wine in

the narrow neck of the bottle. If the wine needs aerating (and some don’t),

it’s better to pour it and then let it rest in the glass for a few minutes.

Myth No 2: Screw top closures signify cheap

wine.

At one time, almost all wine bottles

were sealed with cork but today screw caps have become so reliable that most

everyday wines use them. The majority of Australian and New Zealand wines

use them regardless of quality. Screw caps are preferred by many European

wine producers too. It is only a comparatively tiny percentage of wine

intended for long-term ageing that are thought to benefit from a cork

closure.

Myth No 3:

“Legs” in the glass indicate high quality wine.

You’ve probably seen those rivulets

of liquid that adhere to the inside of the glass. They’re caused by a rather

complex physical phenomenon involving surface tension and alcohol

evaporation and often found in wine with either high alcohol or sugar

content. It’s known as the Marangoni Effect has nothing to do with

quality. A thesis on the subject brought the eponymous Carlo Marangoni his

doctorate degree in 1865.

Myth No 4:

Wine always improves with age.

Most of the wine in the world is

made for consumption within a couple of years. After that it’ll lose much of

its freshness; the taste will start to fade and the wine will sadly become a

shadow of its former self. The majority of wines deteriorate with age. The

exceptions are the small percentage of wines made for ageing, such as top

quality wines from Bordeaux and Burgundy.

Myth No 4: Blended wines are inferior.

Almost every wine is blended. Classic Bordeaux

for example, is usually a blend of at least three grapes. Wine made from a

single grape variety is called a varietal and usually (but not

always) has the name of the grape on the label. However, regulations

allow a proportion of other grapes to be used. In Europe a varietal must

contain 85 percent of the grape shown on the label but in America it’s only

75 percent. Relatively few wines are made entirely from a single grape

variety.

Myth No 5: Red wine should always be served

at room temperature.

This myth implies that all red wines

should be served at the same temperature, which is simply untrue. Both

humidity and temperature have a significant impact on how a wine smells and

tastes. And in any case, what is the temperature of a room? Most red wines

are at their best when the temperature is below 70°F (or 21°C) which is

lower than most domestic temperatures, especially in this part of the world.

Here, red wine should feel slightly cool, but not cold. Full-bodied reds

such as Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot should be about 64°F. Light, fruity

Beaujolais is always served distinctly cool in its home country at about

53°F. For the best advice, look at the back label on the bottle. If in

doubt, cooler is better for the wine will soon heat up in the glass.

Myth No 6: Always drink red wine with

cheese.

Yes, Pinot Noir works well with

Emmenthal or Gruyère, while Edam (AY-dum) and Gouda (HOW-dah) can go well

with Cabernet Sauvignon. But these two Dutch favourites also work superbly

with dry Riesling. Many cheeses taste better with white wine rather than

red. Brie and Camembert work perfectly with Chardonnay, Chenin Blanc or even

Sauvignon Blanc. Blue cheese often calls for sweet white wine and

amontillado sherry will probably go with many varieties of cheese. The best

means of discovery is to have a cheese and wine pairing experiment yourself

and find out what combinations work. Assuming of course, that you have the

time, the inclination and the money.

|

|

Sweet Talk

Banrock

Station Wine and Wetland Centre.

I was in Hungary at the time - Budapest

to be exact - staying at a cheap lodging in a rather run-down part of town.

It was here, one evening that I had my first taste of classic sweet wine. It

was Hungarian Tokay Aszú, the world-famous and somewhat mystical

golden wine known throughout the English-speaking world as Tokay (tock-eye).

It was ravishingly sweet. For hundreds of years it was

the favourite wine of the wealthy aristocracy of Europe, Russia and Poland.

Earlier in the day, I had chanced upon a small wine shop where the

enthusiastic owner persuaded me to buy a bottle. In those days I was not

used to drinking wine regularly and this unfamiliar yet sumptuous wine

turned out to be higher in alcohol than I had expected. Later that night, I

found myself effortlessly levitating inside the vast spaciousness of St

Stephen’s Basilica in Budapest.

To wine enthusiasts, the mention of sweet wine brings

memories of German Eiswein or those two splendid French dessert

wines, Sauternes and the rather lesser-known Barsac, both of which come from

the Bordeaux region. Because of the high sugar content they age well and

have a lovely soft, slightly syrupy texture though they are rarely cloying.

The most famous is

Château d'Yquem

which is regarded with reverence among wine connoisseurs. Vines have been

planted at the château since 1711 and the legendary sweet wines are noted

for their concentration and complexity of taste. They are long-lasting wines

which can develop in the bottle for over a hundred years and some remarkably

old vintages are still available – if you can afford them. You can buy

Château d'Yquem

in Thailand although a single bottle of the relatively recent 2007 vintage

will set you back Bt 55,000. I tend not to drink it very often.

Although sweet wines are usually served only at the end

of formal dinners, they can bring an extra dimension to your desserts at

home. You’ll probably be pleased to know there are cheaper alternatives to

Château d'Yquem.

You can buy a decent bottle of Sauternes at more earthly prices and the

sumptuous, fruity and honeyed Barton & Guestier Passeport Sauternes

is about Bt 1,500 from Wine Now Asia. I’ve also seen the excellent Louis

Eschenauer Sauternes in Villa for about Bt 900.

If you’re looking for something even cheaper to liven

up your dessert, the Muscat grape can come to your rescue. Surprisingly

there are over two hundred different varieties of Muscat (or Moscato) and

they have been around for centuries. In more recent years the grape has been

grown successfully in Australia.

Banrock Station Moscato 2019 (white), Australia. Bt

550 @ various outlets

The curiously named Banrock Station has acquired

something of a reputation for popular fruit-forward wines which are easy on

the palate. This one is a straw colour with attractive hints of green. It

looks inviting and although the first sniff might possibly remind you of

Sprite, more subtle aromas of pomelo and melon soon come through. You’ll

probably pick up the distinctive Muscat aroma too.

This is a lively easy-drinker which tickles the tongue

with its delicate sprizty quality. There’s a surprisingly long and

satisfying finish too; unusual for a wine at this price tag. The wine is

only 5.5% ABV which is about the same as our local beer. You can serve

dessert wines as cold as you dare. I’d prefer this straight out of the

fridge and even then I might give it another twenty minutes in the freezer.

In our sultry climate it’ll soon warm up and allow the aromas to emerge. Not

only will this work well as a dessert wine, you could also try this light

and easy wine as an apéritif.

Deakin Estate Moscato 2014 (white), Australia. Bt

550 @ Wine Connection

This is a really easy drinker and although it comes in

the “sweet” class it would be more accurately described as “semi-sweet”.

Deakin Estate is a relative newcomer to the Australian wine scene. Although

the land was bought in 1967, the company didn’t start producing wine until

the 1990s by which time some of the vines had achieved a venerable age. This

particular wine has won several prestigious awards including a bronze medal

at the UK’s International Wine Challenge.

To my mind, this is a splendid dessert wine if you want

to keep the price as low as possible. It’s a pale yellow wine with faint

hint of lime on the aroma and the distinctive smell of sweet raisins. And

this incidentally is one of the hallmarks of Moscato because as far as I

know, it’s the only wine that actually smells of grapes. The taste has a

delicate acidity and a slightly spritzy quality which makes it delightful

refreshing. At only 6% ABV this wine is remarkably low in alcohol and

there’s an attractively long finish too. There are hints of green apples on

the palate and this proved a perfect match for my home-made apple pie. I use

a recipe from my Scottish grandmother, who in all probability received the

recipe from her Scottish grandmother. The apple pie could have even

been a favourite of Robert Burns. It would be pleasing to imagine that old

Rabbie washed it down with a few glasses of sweet Hungarian Tokay.

|

|

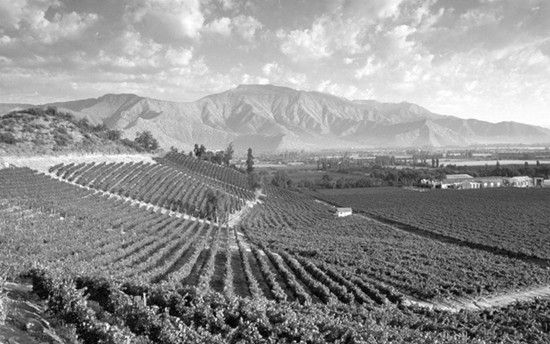

Wine from a long, thin country

The Andes

dominate Chilean vineyards.

In recent months, several bargain-basement Chilean

wines have started to appear, giving locally-produced fruit wines a run for

their money. There’s a good selection at Big C in South Pattaya where they

offer several wines well under Bt 400, most of which were produced and

bottled by the same Chilean company. They can often be recognized by their

outlandish names.

The long, thin country of Chile is confined between the

Andes Mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Its vineyards

lie along an 800-mile stretch of land that has a temperate climate similar

to that of California. You might be surprised to know that they’ve been

growing vines in Chile since the sixteenth century, after the country was

colonized (or invaded, if you prefer) by the Spanish around 1554. You’d

have thought that the Spanish would have encouraged the locals to develop

their own wine industry. But no such luck. During Spanish rule, Chilean

vineyards were restricted in production and the Chileans were instructed to

buy all their wine from Spain. To their credit, most of them didn’t because

they preferred their own wine. In any case, after a rough voyage across the

Atlantic, much of the Spanish wine would probably be oxidized and barely

drinkable. In 1641, in the true spirit of imperial colonialism, the

mean-minded Spanish banned Chile from exporting its wine, but this unfair

ruling was also largely ignored.

The disastrous appearance of the phylloxera epidemic in

mid-19th century Europe brought an unexpected bonus to the

Chilean wine industry. With countless French vineyards in ruin, many wine

makers moved to South America bringing their experience and techniques with

them. As a result, the history of wine making in Chile was largely

influenced by the French, especially the wine-making traditions of Bordeaux.

Even so, during the first half of the 20th century, Chilean wine

was considered rather low quality but substantial foreign investment and

technical advances had an enormous impact with the result that by the end of

the 20th century, Chile was producing some world-class wines.

Quincho Dry White (Chile) Bt 345 @ Big C

They don’t come much cheaper than this, an entry-level

wine produced and bottled in Chile. In case you’re wondering, quincho

(KEEN-cho) is the Spanish word for barbecue. There’s a picture of one

on the back label, which also contains the mystifying expression “Secret Dry

White” though what the secret is I have yet to discover.

The wine is a pale straw colour with an attractive

fruity aroma of honey, pomelo and dusty pineapple, if you can imagine dusty

pineapple. The wine smells more expensive than it actually is and if someone

gave me a glass of this to taste, on the aroma alone I’d estimate the price

to be around Bt 700. And yet, I often see people trying a wine for the first

time and not bothering to sniff it first. It seems such a dreadful omission.

There’s much more fruit on the palate than I expected,

dominated by honey and pineapple. The taste blooms in the mouth too,

something you wouldn’t normally expect with a wine at this price. It’s quite

a dry wine, though the dryness is offset by generous fruit. The acidity is

quite low too and at just 11.5% ABV this wine could be enjoyed on its own.

Quincho Dry Red (Chile) Bt 345 @ Big C

To my surprise, this bottle was closed with a cork,

albeit a synthetic one. Nearly all wine bottles these days are sealed with

the so-called Stelvin closure which is the fancy name for the familiar

screw-cap. The cork was rather reticent too, and I had to ferret out my

strong twin-lever bottle opener which can deal with the most stubborn corks.

I doubt whether a simple cork screw would stand much of a chance.

This entry-level wine is a rich dark red with a

distinctive purple hue. It has an aroma of plums and jammy fruit yet the

body is quite light with plenty of tannin. I know that many people prefer

loads of fruit on the palate but sometimes less is more, especially if you

plan to drink this wine with food. And I hope you do, because to my mind

this is a “food wine”, even if the food happens to be bread and cheese or a

humble beef burger. It’s distinctively dry and the style slightly reminds me

of simple Bordeaux, the sort that the French buy every day in large plastic

bottles.

This wine is significantly cheaper than Mont Clair,

the work-horse wine of almost every bar in town and I thought it might be

interesting to compare them. The wines I mean, not the bars. The Quincho

smells vaguely French whereas the Mont Clair smells like, well,

Mont Clair. The Quincho feels firm, dry and slightly austere

whereas the Mont Clair is slightly fuller, a little less dry and

blended for smoothness. Other than that, there’s not a great deal of

difference between them except fifty baht. And fifty baht is fifty baht.

|

|

Cheap Fizz

Cantina

Montelliana, Treviso.

One of the enduring puzzles about Italian wine is that

the name shown on the label can be one of four different things. It could be

the name of the grape (e.g. Moscato), the name of the wine region (e.g.

Chianti), the name of the town from which the wine comes (e.g. Bardolino) or

in many cases, the name of the wine producer (e.g. Frescobaldi). But one

wine springs to mind that is especially confusing in the nomenclature

department. It’s Prosecco.

In the first place, Prosecco is the name of a style of

wine. It’s often considered a cheap version of Champagne and indeed the

taste profile shows a few broad similarities. But Prosecco is also a place.

Many years ago it used to be a small village but has now been absorbed into

the sprawling suburbs of Trieste and lies about 800 feet above the

Mediterranean up in the extreme north east of Italy. Naturally, they make

Prosecco wine there and have done so since the 16th century, but

in more recent years the main production area for Prosecco has moved to a

region about twenty miles north of Venice. The main town is Treviso.

Prosecco is also the name of the thin-skinned green

grape that makes the wine. Or at least, it used to be until 2009 when the

regional wine authority decided that the official name of the grape should

be Glera, a name by which it had been known locally for generations.

Today the wine is made in nine provinces in the Conegliano-Valdobbiandene

region, a lush, green and hilly area where the best vineyards lie on the

south-facing slopes. Although a small quantity of still wine is produced,

Prosecco is nearly always sparkling or semi-sparkling.

You might wonder why Prosecco is invariably cheaper

than Champagne, especially when they sometimes taste slightly similar. The

reason lies in the bubbles - or rather how they’re made. Prosecco is made

using the so-called Charmat Method which although invented by an

Italian at the end of the 19th century, was further developed by

the French inventor Eugène Charmat in 1907. This method is used all over the

world to produce cheap brands of sparkling wine. In Treviso, it’s often

known as the Metodo Italiano an expression that hardly needs

translation.

The wine is blended and initially fermented using

stainless steel pressure tanks in which the bubbles form during the second

fermentation. This is less time-consuming (and therefore cheaper) than the

more complicated and labour-intensive Champagne Method. Prosecco is often

used as an apéritif but it’s surprisingly versatile and pairs successfully

with a wide range of food. It works well with medium-intensity foods but can

also matches the spicy curries and many other dishes of Southeast Asia.

Cornaro Prosecco Extra Dry DOC,

Treviso, Italy (white) 644 THB @ Villa

This wine comes from the dauntingly named Cantina

Montelliana e dei Colli Asolani, a cooperative of associated

vine-growers founded in 1957. Its vineyards are located on the

southern-facing hills around Montello and Colli Asolani several hundred feet

above sea level. This example comes from the lower end of the price range

though don’t let that put you off. Although it is one of the cheapest

sparklers around, to my mind it’s jolly good value. The wine is a pale straw

colour and has an attractive aroma of apple and peach. At just 11% ABV, it’s

supple and light in body but quite an undemanding wine and not the kind of

thing that requires elaborate descriptions. I’d describe it as a simple

swigger and none the worse for that, because it would be ideal for social

occasions or parties, if we are ever allowed to have them again.

Maschio Prosecco Extra Dry DOC,

Treviso, Italy (white) 644 THB @ Villa

No, it’s not a typing error. The price of these two

sparklers wines is exactly the same, though in England they cost about ten

quid a bottle. Cantine Maschio is one of Italy’s top producers of

quality Prosecco and makes some of the best-selling wines in Italy. This

entry-level wine is almost colourless with subtle hints of green. There’s an

interesting dusty floral aroma with the distinct smell of herbs and a hint

of peaches. The wine is exceptionally light, dryish and refreshing with

plenty of fruit of the palate and a pleasingly rounded taste with delicate

acidity and lively bubbles. There’s also a surprisingly long finish and this

charming little sparkler has a real touch of class. At just 11% ABV it would

make a splendid aperitif, light and easy with not too much acidity.

Incidentally, if the label describes a sparkling wine

as “extra dry” (which both these do) it’s not very dry at all. If you want a

really dry sparkler, look for the word “Brut” on the label. Either

way, Prosecco should always be served cold at around 3-6 °C which is pretty

well out-of-the-fridge temperature. Most wine enthusiasts agree that

sparkling wines should always be served in one of those tall, elongated

tulip glasses, known technically as Champagne flutes. The shape helps

preserve the bubbles for longer and it concentrates the wine’s fruity aromas

at the top of the glass where your nose should be. Unless of course, you are

some kind of alien being, with your nose in an unusual place.

|

|

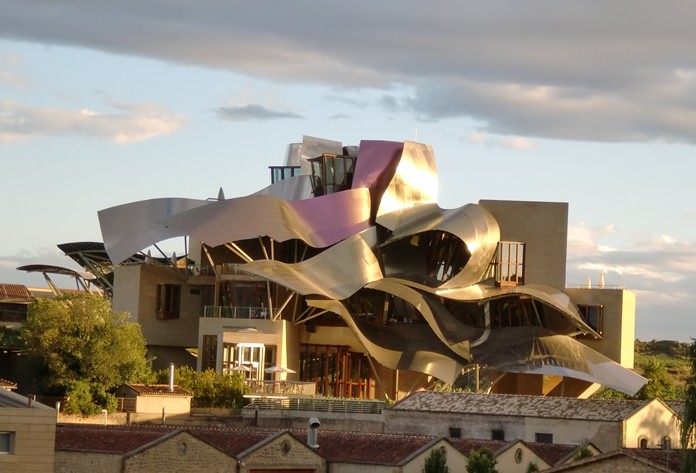

A Sense of Place

The novel design of the Marqués de Riscal hotel.

Yesterday afternoon I was looking through a newsletter

from a wine company in Bangkok and I was mildly surprised to see some Rioja

among their offerings. You might not be familiar with the name and I have to

admit you don’t see them around here very often. For many people, the name

itself is a bit of a challenge. Being Spanish, the “j” is pronounced like

the “ch” in the Scottish word “loch” or a bit like the “ch” that occurs in

many German words. The entire word should come out something like

ree-OCH-ah but I don’t suppose it matters very much how you say it

around here.

You could be forgiven for assuming that Rioja is the

name of a grape, but it’s a place, or more accurately, a wine region. The

name comes from the river that flows through the region, the Rio Oja. Here

they produce some of the best wines in Spain. Rioja lies in the far north of

the country, not far from the border with France and about 120 miles south

of Bilbao. Wine making in this region has a long history, so long in fact

that no one is really sure exactly when it began. The origins of Rioja go

back to the Phoenicians and there is certain evidence that grapes were grown

in La Rioja during the ninth century. In medieval times, La Rioja had many

vineyards which were tended by monks, a common practice at the time. Today

the vineyards cover about 160,000 acres. Most of the region produces red

wine but the whites are also interesting.

I first discovered Rioja about forty years ago and

intrigued by the elegant Bordeaux-shaped bottle surrounded by its

traditional golden wire mesh. I took the bottle home and thus began a long

love affair with this splendid wine which, along with Sherry, seems to me

the epitome of Spain. The Bordeaux-shaped bottle is perhaps not a

coincidence because at first the wine reminded me of Cabernet Sauvignon. But

there was something else. It reminded me of Spain, the gloomy interiors of

the country houses, the dark and heavy furniture and the rich textures of

traditional Iberian fabrics. The wine had a “sense of place” which I found

captivating. Perhaps it’s something to do with the grape variety. You see,

Rioja’s dominant grape is the Tempranillo, the great red grape of Spain.

It’s been grown there for over two thousand years and shows up all over the

country with the result that it has several local names including Abundante,

Tinto Fino and Tinta de Toro. Sometimes another grape, the garnacha (known

in France as the Grenache) as added to Rioja to create a richer fruitier

taste. In 2007, the wine regulating body for the Rioja region decided to

allow several more local grapes to be used in the making of Rioja.

Young, red Rioja is a dark wine with medium acidity,

substantial tannins and sometimes hints of jam and red fruit. Older wines

have a complex aroma with hints of vanilla and coconut which comes from

ageing in American oak. Some of the finest Riojas are, to my mind, almost on

a par with good Bordeaux and certainly share some of the taste qualities.

These older wines often have a silky, smooth texture brought about by

several years maturing in oak barrels.

Although Rioja is produced in different parts of the

region, that doesn’t really concern us here. It’s more important for the

buyer to know the four quality levels of Rioja. The entry level is simply

labeled “Rioja”. This has minimal ageing but is low in tannin and high in

fruit. If you enjoy light fruity wines, you’ll probably enjoy it. The next

level up uses the word “crianza” on the label and it spends a year in oak

and a few months in the bottle before it can be sold. This wine has more

body and often hints of oak. The next rung of the ladder uses the word

“reserva” and these are wines are of noticeably higher quality, having had

three years in the barrel. Wines at the top of the tree are allowed to use

the words “gran reserva” on the label. These are among the best Riojas that

you can get and are required to have at least two years in oak barrels and

three years in the bottle. If you are into beef steaks, this is a wine to

try with them.

Several excellent

brands of Rioja are available in Thailand and the widest choice comes

through online sources. Marqués de Riscal have been producing

top-class Rioja since 1858 and the winery also has a

luxury

hotel on site, designed by Frank Gehry using methods he previously employed

in the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

Marqués de Cáceras is also an old-established

company and you can obtain their

Rionja Crianza for under 900 baht. Wine Connection has the Federico

Paternina Banda Azul Crianza for under 600 baht, which is an excellent

bargain. Wine Garage sells the CVNE Rioja Crianza for Bt 900 and the

excellent Contino Rioja Reserva for Bt 1,900. Wine Garage also has an

unusual white Rioja, the CVNE Monopole at Bt 975. I first tasted the

1968 vintage of this wine sometime in the late 1970s and it had turned into

a beautifully balanced, dry and elegant wine. I have not tasted recent

vintages, but it is sure to make an interesting change from Chardonnay.

Rioja wine has so much to offer and so easily available here that it would a

shame not to try some of them.

|

|

Avoiding Expensive Mistakes

(Photo by Nenad Maric.)

by Colin Kirkpatrick

A few months ago, before the Days of the Great

Pandemic, I was having an evening meal with some friends at an Italian place

in Bangkok. There were several wines on the table including a bottle of

Cabernet Sauvignon. Towards the end of the meal, someone ordered a desert, a

kind of Italian apple and lemon pie with lashings of cream. To my

astonishment he reached for the Cabernet Sauvignon, poured himself a glass

and then happily swigged it with the desert. I assumed that a fuse must have

blown in his gustatory system for the disastrous combination of dry, tannic

wine, sweet apples, lemon and cream would have tasted revolting. The

flavours must have been fighting each other to the death.

You probably know of several food and drink

combinations that just seem that they don’t work. Could you for

example, imagine eating a fried egg with a glass of rich, fruity Merlot? The

thought makes me cringe. There might be a remote possibility that fried egg

and Merlot is a taste made in heaven just waiting to be discovered but I

somehow doubt it. Some wine enthusiasts claim that you can drink champagne

with fried eggs because the acidity in the wine cuts the palate-coating

taste of yolk. But it would just feel wrong. To my mind, the only

successful partner to a fried egg is a cup of tea.

Food and wine have been close companions for centuries,

because generally they go together so well. But there are a number of

combinations that simply don’t work largely on account of the chemistry.

Wine is expensive enough, without wasting a good bottle on the wrong food.

It could ruin the evening. The whole business of food and wine pairing might

seem like a minefield, but it boils down to a simple fact: you need the wine

and the food to complement each other so that they both improve in each

other’s company.

In a restaurant, choose a wine that fits your budget.

And play it safe rather than risk a dodgy experiment with the unknown,

especially if the unknown costs Bt 3,000 a bottle. I usually prefer to keep

things simple with three rules of thumb: (1) match the weight and texture,

(2) match the intensity, and (3) either contrast the flavours or let them

complement each other.

If you were to drink a young white with a rich and

fully flavoured beefy dish, the wine would probably taste thin and watery.

Delicate flavours of fish dishes need a light, delicate wine. A hefty

full-bodied red would overpower the food completely and render it pretty

well tasteless. Even so, there’s no point in drinking dry-as-a-bone

Sauvignon Blanc with lightly cooked shellfish – a classic combination by the

way - if you loathe and detest Sauvignon Blanc.

And talking of fish, you may recall that much-quoted

saying, “white wine with fish; red wine with meat.” It’s an

over-simplification of course. Some light reds work well with rich,

assertive fish dishes and many whites work well with veal or chicken. While

some reds take on an unpleasant metallic quality when paired with fish,

grilled salmon works really well with Pinot Noir. Some of the classic food

pairings, tried and tested over generations are worth bearing in mind:

Chablis or Muscadet with oysters; red Burgundy with coq au vin;

Cabernet Sauvignon with steak; Sauternes with foie gras and

Chardonnay with lobster. If you can afford caviar, bring out the Champagne.

For many of us, food choices are rather more mundane.

What about fish and chips for example? You might be surprised to know that

Champagne goes well with this British favourite, or Prosecco if you’re on a

budget. My own choice would be Sauvignon Blanc or Pinot Grigio though I’ve

heard that Chenin Blanc goes a treat with mushy peas.

For beef burgers, chose Pinot Noir or a fruity Merlot.

Hot dogs go well with a cold fresh dry rosé or even a spritzy white. Veggie

omelets complement light dry whites like Chablis or Soave but more robust

omelet fillings need a simple country red. Indian food generally calls for

low alcohol wines and Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc or Gewürztraminer are

appropriate choices.

Thai food generally works well with light dry whites

such as Pinot Grigio, Soave, Chenin Blanc or dry rosé. Leave the reds on the

shelf. The choice of wine with chicken depends on how the meat cooked, but

generally rich dry whites or light reds work well. Pinot Noir is the classic

wine choice for duck.

Wine and cheese have long been traditional partners but

there’s a persistent myth that cheese will go with almost any red wine. I

disagree. Full-bodied reds and soft cheese (such as Brie or Camembert) don’t

work because the tannins make the cheese taste chalky. Dry, crisp whites are

far more suitable. Save the red for richer items. Riesling and Chardonnay

usually go well with Swiss cheese. Riesling also works well with two popular

Dutch cheeses, Gouda and Edam. British mature Cheddar can be a problem, and

I’ve read all sorts of suggestions that range from Californian Zinfandel to

late-bottled Port. My own preference, especially for a summer lunch, would

be a cold beer.

|

|

Over the Hill

Bulk wine on the move.

The other week, someone asked me why there’s never a “best

before” date on bottles of wine. It’s a good question. After all, they

appear on almost all other consumables, even cans of dog food. So why not

wine? Some boxed wines have the packing date stamped underneath but it’s

often in minuscule print and you might need a magnifying glass to find it.

You might be surprised to know that the concept of “best before” dates is

relatively recent. They were first introduced in the UK in the 1950s but

didn’t become established until about twenty years later. Contrary to

popular belief, they are only approximate and according to Smithsonian

Magazine, food expiration dates are often simply made up by the

manufacturer. A few countries don’t use them at all.

There is a persistent myth that wine

improves with age. Some optimistic people believe that if they leave a

bottle of cheap plonk in the cupboard for a few years, the Wine Fairies will

get to work and somehow turn it into liquid gold. Needless to say, it’s

complete nonsense. Cheap plonk will always be cheap plonk however long it

languishes at the back of your cupboard, which incidentally is the worst

place you can possibly store it. Rather than improve, it will soon begin to

decay and you will left with a dismal thing resembling vinegar. It might be

useful for cleaning out the gearbox of a tractor, but not much else.

A few months ago, one of my friends

offered to bring a “special” bottle over for us to try. “It’s been in the

cupboard for years,” he enthused. “So it should be pretty good by now.” My

heart sank. The wine turned out to be a once-decent Sauvignon Blanc but the

label revealed that it was over seven years old. I tentatively opened the

bottle and was greeted by the distinct aroma of rotting vegetables. The wine

had turned a light brown and was undrinkable. My friend was clearly

disappointed that his “old” wine was not just over the hill, but half way

down the other side. Even the dogs turned it down.

You see, the vast majority of wine is

made for early consumption, ideally within a year or so. Commercial table

wine has a shelf-life of about two or three years, assuming that the storing

conditions and temperature are appropriate. If you see ordinary table wine

in the supermarket older than four years, it’s often safer to leave it on

the shelf. Wine that comes in boxes or bags has a shelf-life of about a

year. Some companies claim that once opened, a boxed wine is drinkable for

up to six weeks but I’d take that with a pinch of Himalayan mountain salt.

In the case of top-quality Bordeaux or

Burgundy intended for long-term ageing, “best before” dates would be

pointless. When a fine vintage is bottled, no one is absolutely certain when

it’ll be at its best - it could be decades into the future. The only way to

check on a fine wine’s development is to taste a sample bottle from time to

time, which in fact is exactly what happens.

You’d have thought that with ordinary

table wines it would be easier to define a “best before” date. But not so.

There are too many variables over which the wine-maker has no control.

Unlike other food products, wine can be severely damaged by careless

handling. A bottle of European table wine for example is likely to have a

longer life if stored correctly in its home country than an identical bottle

that has been transported by various means to a shop on the other side of

the world.

I’ve found that in these parts, the two

most common wine problems are oxidation and heat damage, despite the fact

that nearly all commercial wines are heat-stabilized during the winemaking

process. Wine writer Laura Burgess believes that the threshold for heat

damage begins at about 70°F (21°C). Wine damaged by heat tastes rough or

acidic and red wine acquires a kind of jammy sweetness, sometimes with

astringent tannins.

Oxidized wine is a more common problem,

especially in restaurants. Once a bottle has been opened and partially used,

the remaining wine oxidizes rapidly. It’s the same chemical process - more

or less - that changes the colour of apple slices from white to brown. And

like apples, white wines go brown too, whereas reds take on a sherry-like

aroma of stewed fruit.

Of course, a bottle of wine does not

suddenly “go off” because it’s a gradual process. The aromas and flavours

slowly fade and the freshness diminishes. Chemical changes sometimes cause

unwelcome odours to develop. There is no single cut-off date. And all this,

in a rather small and simplified nutshell, is why there can be no reliable

“best before” date for wine.

To avoid buying a duff bottle in the

supermarket, remember that as far as commercial wine is concerned, younger

is safer. And let’s face it; a lot depends on the experience of the

consumer. Would you really notice for example, if your glass of wine was

mildly oxidized or heat damaged? Possibly not.

Not long ago, I was in a local

restaurant with a group of friends (yes, I do have some). We’d opted for a

large carafe of house red but it turned out to be ever-so-slightly oxidized.

The faded colour and dodgy aroma gave it away. But my merry friends were

clearly none the wiser and knocking it back with abandon. It would have

seemed churlish to make a comment.

|

|

The Green and Pleasant Land

Hush Heath vineyard in Kent.

In 2002, the British Broadcasting Corporation organized a

poll to find out who were considered the greatest British people who ever

lived. You can probably guess a few of them yourself. It turned out that

William Blake, the slightly eccentric English poet and painter was placed at

Number 38. If these things interest you, I shall leave you to find out who

the others were but sadly, I am not among them.

William Blake was unrecognized during

his lifetime but he’s now considered a key figure in Romantic art and

poetry. It is he who gave us the expression “England’s green and pleasant

land” which first appeared in the rather surreal and supposedly prophetic

poem of 1804 entitled Jerusalem. It was written when Blake was living

in his cottage in Felpham, a small village near the Sussex town of Bognor

Regis. The village lies in the heart of England’s wine country.

Wine making was introduced to Britain

by the Romans, who occupied the country for well over three hundred years.

The Domesday Book of 1085 lists over 40 vineyards in England and by

the time Henry VIII was crowned at the turn of the 16th century

there were 139 vineyards in the country. Today there are more than 500 in

England and also a couple of dozen in Wales.

For a variety of economic and political

reasons, English wine had entered a dark age during the 19th century

and by the First World War, wine production had ceased completely. Although

attempts were made to kick-start the wine industry in the 1930s, it wasn’t

until the 1960s that it started to get back on its feet.

In subsequent years things improved,

largely due to increased expertise, climate change and market demands.

Today, many parts of southern Britain are dry and warm enough to grow high

quality grapes and the soil seems to suit them too. It’s in the interest of

farmers as well, because grapes produce far more income per acre than

traditional English crops such as wheat.

Generally, cool-climate grapes are best

suited to England, including Seyval Blanc, Reichensteiner and the

cross-breed variety Müller-Thurgau. Bacchus is a German hybrid white grape

created in the 1930s and it’s the grape of choice for many English

wine-makers.

Initially, only white grapes could be

grown there, but the warmer climate is allowing the production of red wines

too. The red grapes Pinot Noir, Gamay and Dornfelder are now appearing in

English vineyards.

The counties along the southern coast -

Kent, Sussex and Hampshire - are the home of some of England’s best-known

vineyards. Kent currently has the largest area under vine, its largest

producers being Gusbourne Estate and Chapel Down.

England is also producing world-class

sparkling wines from traditional Champagne grapes such as Chardonnay, Pinot

Noir and Pinot Meunier.

Award-winning sommelier Marc Almert

writes, “British sparkling wines are currently on everyone’s lips in the

international wine world. On average, the climate in southern England today

is like that of Champagne twenty years ago. The soils of the vineyards

around Sussex and Kent also have high lime content, similar to that in

Champagne. No wonder that England is currently one of the most dynamic

sparkling wine regions in the world.”

The French Champagne companies must

have been eyeing this English success with interest, to say the least. Three

years ago, the distinguished French Champagne house Taittinger planted its

first vines in 170 acres of farmland near Selling Court Farm in Kent. Some

of the locals may have wondered whether this was a portent of a second

Norman invasion.

Many English wine companies have been

tremendously successful. One of them is Nyetimber Wines. Thirty years ago,

Stuart and Sandy Moss planted a vineyard in the district of Nyetimber in

West Sussex, not far from where William Blake wrote his famous poem. Their

first wines were released in 1997 and promptly won a Gold Medal at the

International Wine and Spirit Competition. The company has gone from

strength to strength and a few weeks ago announced a major planting of over

100 acres near the village of Thurnham in Kent. Two hundred thousand Pinot

Noir and Chardonnay vines have already been planted.

So which are the best English wines to

look out for? Well, I am afraid the bad news is that you’ll probably have to

go there to buy them. As far as I am aware, there are no UK wines yet

available in Thailand. If however, you can persuade someone to bring you a

sample when all the current problems subside, there are several excellent

outlets in the UK all of which offer online service.

Majestic Wine is a well-established

company that offers an excellent selection of English wine. Other important

outlets are Grape Britannia, Elizabeth Rose English Wines, Hawkins Brothers,

The British Wine Cellar, The English Wine Collection and Hennings Wine.

These companies together offer an incredible selection of fine wine. If you

are planning a future trip there, be sure to seek out some of the superb

wines that the UK has to offer.

|

|

North of the Border

Sainte-Eulalie de Cruzy. (Photo: Francois Werth)

Next time you visit Toulouse to see how they’re getting along with your

custom-built Airbus, you can pass the time by renting a car for the day. If

you were to drive down the A61 or the A64 for a few miles, you would soon

find yourself in the Comté Tolosan.

This is a massive wine-growing region that covers the

whole of South-Western France and reaches down to the Spanish border. They

produce more than five million gallons of wine every year there using the

usual well-known grape varieties but also many local varieties.

You might never have heard of Gros Manseng, Loin de

l’Oeil, Duras, Fer Servadou or Négrette but they all hang out in Comté

Tolosan and almost nowhere else in the world. The region is a part of the

so-called Aquitaine Basin, which includes the plains that fall between the

Pyrenees, the Massif Central to the East and the Atlantic Ocean to the west.

I don’t want to bore you comatose with technical stuff,

but there’s something you need to know. Between 2006 and 2012 the French

revised their traditional system of wine classification. If this is news to

you, please sit up and listen carefully because I am not going to bother

explaining it all again. In a nutshell, the result was that wines previously

classed simply as Vin de Pays (“country wines”) had to show the

rather more prosaic classification of Indication Géographique Protégée

(IGP) on their labels. The rock-bottom category of Vin de Table

(which hardly needs translation) was changed to Vin de France. The

top designation, which used to be Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC)

was replaced with Appellation d'Origine Protégée (AOP). In 2011, the

rather useful classification of Vin Délimité de Qualité Supérieure (VDQS)

which had been introduced in 1949 was given the old heave-ho and

unceremoniously chucked out altogether.

Cuvée Montplo,

Comté Tolosan IGP (white), France

Both today’s wines hail from the strangely-named

Domaine Montplo which lies to the east of Comté Tolosan in the region known

as l’Hérault (lair-OH). It stretches from the shores of the

Mediterranean to the Cévennes Mountains in the north. At its centre lies the

ancient town of Béziers, known among other things for the local obsession

with bullfighting. Domaine Montplo is tucked away in Cruzy, a small wine

village about thirty minutes’ drive north of Narbonne.

At first sniff, the wine smells a vaguely like a

Chardonnay but it’s actually a blend of Colombard and Ugni Blanc. You may be

unfamiliar with Ugni Blanc, but it hails from Italy, where it’s known by the

more familiar name of Trebbiano. This wine is pale yellow with hints of

green and it has a lovely floral aroma of pineapple, melon, citrus fruits

and honey.

When the air gets to the wine, you’ll find that both

the aroma and taste open up beautifully. Comté Tolosan white wines are known

for their aromatic qualities and this one is no exception. It has a soft,

seductive and almost creamy mouth-feel, plenty of tropical fruit up-front

and hardly any acidity. It’s not quite as dry as the proverbial bone, but

it’s dry nonetheless and there’s a touch of pleasing acidity on the long

finish.

It would work well with seafood but would be perfect

with a simple salad. This is a really lovely wine and at only 11.5% alcohol

content, I’d be quite happy to drink it on its own all evening. In fact, I

think I will.

Domaine de Montplo, Pays d’Hérault IGP (red), France

The vineyards of Domaine de Montplo lie to the west of

Béziers, on stony, clay-based soil. They are planted on hillsides at 200

metres altitude and benefit from proximity to the rocky scrubland and its

wild herb aromas. Mind you, the aroma of this

attractive, dark red wine is a bit shy at first. But if you’d been stuck in

a bottle for two years, hauled from France to Thailand then dumped in a

storeroom for a couple of weeks, you’d probably feel a bit withdrawn too.

Eventually, when the wine has had some air contact, you’ll pick up fruity

aromas of blackberry, plum, blackcurrant and raspberry. It’s worth waiting

for.

The wine has a beautifully

soft texture with loads of fruit on the palate. It’s balanced, well-rounded

and perfectly dry with a foundation of supple tannins. There’s a very

satisfying long, dry finish with just enough tannin to remind you that this

is a real French wine, not a Californian crowd-pleaser.

It’s made from two local

grape varieties, Carignan and Grenache, the second of which also happens to

be one of the most widely planted red grapes in the world. At just 12%

alcohol content it would make an excellent partner for light meals,

especially with cheese.

By the way, both these wines

come with a very welcome screw cap (or “Stelvin closure”, if you want to

impress your friends). I’ve grappled with so many corks in my time that a

screw cap comes as a great relief. Yes, I know it lacks a certain mystique

and romance, but there again, so does an Airbus.

The wines described in this column

are generally available in Thailand, either from local outlets or from

online wine suppliers.

PHOTO:

|

|

Rose-Tinted Spectacles

Provence: home of fine rosé.

It’s a curious expression when you come to think about it,

yet I suppose most English speakers know what it means. I think I was

wearing them when I first visited Thailand over thirty years ago. Everything

seemed so fresh, new and inviting; everyone warm and friendly and I became

enchanted by the country. I don’t think I even noticed the dirt and piles of

rubbish in the grubby sois of Bangkok. But why the colour “rose” I wonder?

In 2015, psychology researchers Andrew

Elliot and Markus Maier wrote, “Given the prevalence of color, one would

expect color psychology to be a well-developed area. Surprisingly, little

theoretical or empirical work has been conducted to date on color’s

influence on psychological functioning, and the work that has been done has

been driven mostly by practical concerns, not scientific rigour.”

Even so, in popular imagination colours

often tend to be associated with human feelings or emotion. Past

experiences, cultural influences, personal taste, and other factors probably

influence how individuals respond to particular colours. In many cultures,

rose-pink is often considered a peaceful colour associated with love,

kindness, and femininity. Remember the old wives’ adage about “blue for a

boy and pink for a girl”? It seems that colour associations are reinforced

from an early age.

So what about pink wine? It’s usually

described as rosé, a French word meaning much the same thing. If you

are of a certain age you may recall Mateus Rosé, a brand created in

1945 and designed for mass market appeal. It’s sweet and slightly fizzy and

still going strong in its distinctive flask-shaped bottle. Rosé wine has

come a long way from being the simple glugger of the 1970s, when Hugh

Johnson wrote, “Buy the cheapest rosé you can find, for there is not much to

choose between them.” Today of course, that is no longer true. Rosé has

achieved popularity largely because it has become so much more interesting.

It is no longer chic to be sniffy about rosé. In France, more than one in

five bottles of wine sold is rosé where it has become a popular light drink

or apéritif.

Anyway, let’s get to business. By

definition, rosé is a type of wine that incorporates some of the colour from

the skins of red grapes. Almost any variety of red grapes can be used to

make it, though Shiraz and Grenache are popular among winemakers. Rosé is

aromatic, light and fragrant (or should be) with reminders of fresh cut

flowers and ripe red fruits like strawberry and cherry. Sometimes there are

tantalizing hints of delicate floral aromas, oranges, grapefruit or lychee.

Rosé works well with most foods and for something to accompany a light snack

it’s perfect, especially when served ice-cold. European rosé tends to be

dry especially the dry-as-a-bone rosé from the South of France. If you

prefer dry wine, stay with European rosé because many New World examples are

usually on the sweet side. Many companies also make sparkling rosé.

You might be surprised to know that

both red and white grapes produce clear, colourless juice when pressed. The

colour comes almost entirely from the grape skins. There are several ways to

make rosé but the most common is known as maceration (or soaking),

which involves leaving the skins to soak in the newly-crushed grape juice

for a limited amount of time. It can be anywhere between six to forty-eight

hours, depending on the style of wine needed. And incidentally, rosé is

rarely a simple pink. The colour can range from a pale “onion-skin” orange

to a vivid near-purple, depending on the grape used and the length of the

maceration.

You may be wondering where you can buy

rosé in this neck of the woods. Rosé should always be consumed when it’s

young and fresh, so it’s generally safer to buy it where you can be

reasonably sure of a rapid turnover. Wine Connection has several branches in

Pattaya and they have a few interesting rosé wines on offer including a

couple of typical dry ones from the South of France. The online wine company

Wine-Now.Asia appears to have a splendid selection of rosés from all over

the world. There are many interesting examples under Bt 750 including the

excellent Paul Jaboulet Parallèle 45 Rosé. If you’re prepared to fork

out up to Bt 900 there some even more tempting offers from this company.

You might be surprised to know that

rosé is also made in Thailand. One of the entry-level examples is Monsoon

Valley Rosé which comes from Siam Winery. A bit further up-market is the

excellent PB Valley Khao Yai Reserve Rosé which is a lovely dusky

pink with tantalizing hints of orange. One of the most fascinating Thai

rosés I have come across is the award-winning GranMonte Sukana Syrah Rosé,

made from 100% Syrah grapes grown in Central Thailand. It’s a lively and

refreshing wine with delightful fruity aromas and available online via the

GranMonte website at about Bt 940. This is one of the best examples of a

quality Thai rosé that you are likely to encounter. But don’t forget, always

serve rosé really cold.

|

|

Clochemerle Country

Gamay grapes on the vine.

If you’re over a certain age, you may recall the French

satirical novel Clochemerle. It was written by Gabriel Chevallier and

first published in 1934 though the English translation didn’t appear until

some years later. The book is set in a fictional Beaujolais hamlet of the

same name and the story revolves around the local squabbles surrounding the

installation of a public urinal. In 1972, BBC television produced a popular

series based on the novel, much of it filmed on location in France. The

British viewers must have thought they were being given a glimpse of The

Real Beaujolais but the location sequences were actually filmed in the

village of Colombier-le-Vieux over ninety miles to the south in the Ardèche

region.

The area known as Beaujolais (boh-zjuh-LAY)

lies south of Burgundy and extends about thirty-five miles from the rolling

hills south of Mâcon to the flatter lands north of Lyon. The region was

first cultivated by the Romans, who sensibly planted vines along their

trading route up the Saône River valley to provide sustenance for travelers.

Unlike the red wines of Burgundy which rely totally on the Pinot Noir grape,

Beaujolais is made solely from Gamay, a purple thin-skinned grape which is

low in tannins. Almost all the wines made there are red, full of fruit, easy

to drink and food-friendly.

Beaujolais Nouveau

is wine which has been fermented for just a few days and released on the

third Thursday every November. Technically it’s known as a vin de primeur

and it has become famous for the races by distributors to get the first

bottles to different consumers around the world. Contrary to popular belief,

it’s not a modern fad because the origins of Beaujolais Nouveau date back to

the 19th century

when the young became all the rage in Paris. These sprightly wines are meant

to be enjoyed as young as possible, when they’re at their freshest and

fruitiest.

In his splendid book Adventures on

the Wine Route, Kermit Lynch writes, “What a concept, downing a newborn

wine that has barely left the grape, a wine that retains the cornucopian

spirit of the harvest past.” But Beaujolais has changed, much to the chagrin

of the Old Guard. Fifty years ago it was simpler stuff, sometimes a bit

rough at the edges and rarely exceeded 10-11% alcohol content. Today it is

more likely to be 12.5% and crafted for more sophisticated customers who

demand fuller flavour, smoothness of texture and – let’s face it - a bit of

class.

The quality levels of Beaujolais are

easy to understand because there are only three. The lowest is labeled

simply Beaujolais and it’s a basic blend using cheap grapes from

anywhere in the region. A wine labelled Beaujolais Villages is at the

middle level and covers blends from any of thirty-nine small villages in the

northern part of the region. Wines from these villages are considered

superior to ordinary Beaujolais in that they have more complex aromas and a

more satisfying concentration of flavours.

The top-level wines are known as Cru

Beaujolais and come from just ten villages in the foothills of the

Beaujolais Mountains. The hilly terrain, granite base and sandy clay soil

provide an ideal environment for Gamay to express itself to perfection. The

name of the individual village usually dominates the label and sometimes the

name Beaujolais is omitted altogether. These are the most interesting

Beaujolais wines you can buy because each village produces wine with its own

special characteristics. In Thailand you might – if you’re lucky – come

across Brouilly, Chénas, Fleurie, Morgon and Moulin-à-Vent. These are

longer-lasting wines and unlike ordinary Beaujolais, they can keep for

several years.

I once found some half-bottles of quite

old Moulin-à-Vent in an old and dusty wine shop in South London. They were

well over ten years old but still youthful by Moulin standards – some of

which can age for decades. The wine was superb: rich dark fruit, earthy

woodland aromas and a stunning velvety texture. The next morning I drove

back the shop and bought the few bottles that they had left.

You’re unlikely to come across such

treasures in these parts but if you buy Beaujolais, look out for the

respected names of Bouchard, Drouhin, Duboeuf and Jadot. If you’ve not yet

had to opportunity to taste Beaujolais, you might be wondering what it

tastes like. Well, Beaujolais is made to be enjoyed young, when it’s full of

youthful exuberance. Part from the distinguished Cru Beaujolais, most

of the wines are typically youthful, light-bodied and with fresh acidity.

Beaujolais tends to have soft, jammy aromas of red fruits such as

strawberry, raspberry or redcurrants and the better quality ones come with

forest aromas which might even remind you of Pinot Noir. They usually have a

gentle mouth-feel and light tannins. These charming wines make a lovely

accompaniment for summer or al fresco meals. Ordinary Beaujolais goes

perfectly with light meals, omelets, vegetarian dishes and salads and even

with light chicken dishes. But do as the French do, and always drink it

slightly chilled. Of course in that part of France, it’s the daily swig for

in those rustic regions they consume little else.

|

|

Air Power

Decanting wine.

One of the most heated arguments among wine

enthusiasts is not really about wine at all. It’s about whether you should

pour it directly from the bottle into the glass, or whether you should first

pour it into a decanter. Red wines that have been in the bottle for several

years sometimes develop sediment. White wines rarely do, though tartrate

crystals are sometimes found in older whites. There’s nothing wrong with

sediment, it’s just the dead yeast cells and other tiny insoluble fragments

that settle to the bottom of any wine container. However, it looks a bit

unsightly and few people like to encounter black grit at the bottom of their

glass. Decanting is the process of separating the wine from the sediment.

But more of that in a moment.

Aeration is a simple

process which enables the oxygen in the air to react with the wine and

enhance the flavors and aromas. Some people (and many waiters) seem to

believe that having opened the bottle, it should then be left to stand for a

couple of minutes “to breathe”. This is nonsense, and I shall tell you why.

When the bottle is standing on the table, only the wine in the narrow neck

of the bottle is exposed to the air. This tiny surface area is far too small

to make any significant difference. It’s better to simply pour the wine into

the glasses and let it rest for a few minutes.

If you are at home

rather than in a restaurant, you can aerate the wine by tipping the whole

lot into a wine jug or decanter. But if you drink only a couple of glasses

at a time rather than an entire bottle, consider buying a device called an

aerator. There are two main types and both are inexpensive. One type is held

above the glass while you pour the wine through it, but the process can be

messy especially if your eyesight is not so good. It’s probably safer is to

use the other type of aerator that fits into neck of the bottle and also

acts as a stopper.

Aeration is something

of a battle-ground among some wine experts. Professor Emile Peynaud, the

distinguished French enologist believes that any oxygen damages wine

and you should always pour wine straight out of the bottle into the glass. I

have to say that few other experts would agree with him. I usually taste the

wine first before I decide whether to aerate it. Nine times out of ten, I

prefer aeration unless of course it’s sparkling wine which is never

decanted nor aerated. If you use boxed wine, a decanter is pretty well

essential. It doesn’t need to be an expensive one either. I use plain,

simple glass decanters, made by Ocean and available at any decent kitchen

shop for well under 100 baht each. They come in a variety of sizes. If you

are sharing a bottle with two other people, you can pour the entire contents

into three 25cl decanters. This ensures that everyone receives their fair

share and avoids unseemly fist-fights later.

You don’t need to pour

cheap wines gingerly as though they’re liquid gold, once you’ve got the top

of the bottle over the decanter, just let the wine slosh in, so that the

oxygen can really get to work. This is probably best done in the kitchen

rather than at the table, in case you make a complete hash of it. And here

you may detect the voice of experience.

Nearly all the world’s

wine is made for early consumption and not intended for ageing, so sediment

is unlikely in any wine you pick up at the supermarket. Unless you drink

vintage port or old and expensive wines from Bordeaux, Burgundy or Italy

you’ll probably never need to bother decanting. There’s no mystique in

decanting, but it does require a little practice. If your wine has been

stored horizontally (which it should have been) place the bottle upright at

least a day before opening. This ensures that any sediment settles at the

bottom. When you’re ready, gently remove the cork, grasping the bottle as

steadily as possible. Then hold it over the neck of the decanter (the

bottle, not the cork). Pour in the contents gently and steadily until the

bottle is almost horizontal. As soon as you see sediment approaching the

neck of the bottle, stop. It’s easier if there’s a bright light behind the

bottle. Traditionally, a candle was used (no doubt with many cases of burnt

fingers) but a small LCD torch is even better.

I suppose in the end,

while decanting is a necessary chore for many older red wines, aeration is

partly a matter of personal taste. If you prefer your wine tasting tight and

firm, pour it straight from the bottle, but if you want it to open up a bit

pour it first into a decanter or wine jug. You may want to use a decanter

when the wine bottle has an especially ugly or cheap-looking label, or you

may want to conceal the fact that you are dishing up cheap plonk. Far be it

from me encourage dishonesty, but an elegant decanter will help to preserve

your guilty secret.

|

|

Pizza Wine

Pizzeria in Capri (Photo: Elijah Lovkoff).

The entrepreneur, restaurateur and author Peter Boizot once

wrote, “After one of his rapturously received performances at the

Metropolitan Opera in New York, the great tenor Enrico Caruso was asked for

his secret. How did he control such power and passion and project such lush

sweeps of melody? Looking his questioner straight in the eye, Caruso replied

È la pizza, la pizza, caro mio. (“It’s the pizza, the pizza, my

dear.”) Caruso was paying unusual tribute to a great national dish of his

own country which was not particularly well-known outside Italy at that time

– except, as it happened in New York itself, where Italian immigrants had

introduced the tradition of the pizza.”

Many years ago in London, I used to

visit some of the original Pizza Express restaurants which were

founded by Peter Boizot in 1965. One of them was a stone’s throw from the

British Museum in a dark, narrow side street that probably hadn’t changed

very much since the time of Charles Dickens. On one occasion at the

restaurant, an earnest young Spanish waiter informed me that because there

were some slices of mushroom on my pizza, I should be drinking white wine

with it, not red. This of course was absolute and total nonsense and exuding

as much sweetness and charm that I could muster, I told him so.

Wine has always been the traditional

accompaniment to pizza. Indeed, in many European countries, wine has always

been a staple item at the dinner table partly because it was considerably

safer to drink than water. Pizza was sold in the taverns and on the streets

of Naples in the sixteenth century, though Peter Boizot hinted at its

Neolithic origins when he wrote, “in its simplest form, the pizza…could have

been invented by anyone who had learned the secret of mixing flour with

water and heating it on a hot stone.”

Pizza has come a long way since then

but it remains a simple dish, though it can have countless variations and

fascinating flavours. It’s relatively easy to make too. I’ve been making my

own for years, though the dough-kneading process can be a bit of a bore. To

my mind, simple food needs simple wine. And wine it must be, because pizza

cries out for wine. It’s unlikely that people in sixteenth century Naples

spent much time discussing the most appropriate wines. They’d simply drink

whatever happened to be available locally. And there would have been plenty

of choice, because Naples lies in Italy’s Campania region where wine has

been produced since the 12th century

BC. It’s one of Italy’s most ancient wine regions with a vast number of

grape varieties, some of which are found almost nowhere else on earth.

Today’s wines from the Campania region tend to be fruit-forward and youthful

and many of them would make perfect matches for pizza. However, you’ll

probably be hard-pressed to find Campania wine in these parts.

The ideal pizza wine is what the

Italians call vino da pasta, which is any inexpensive light table

wine knocked back with almost every meal and usually served on the cool

side. Yes, I know that some people prefer to drink beer with pizza, but if

you must, try to find a strong Italian beer like Nastro Azzuro.

With simple food like pizza, almost any

crisp, dry, wine will do. It can be red or white but if it also happens to

be Italian, so much the better. Italian wine is made for food. Although some

people like hearty wines with pizza, I prefer to drink light-bodied wines

regardless of the toppings. My preference would be a Valpolicella or a

Bardolino (red) or a crisp dry Frascati or Soave (white). I should stress

here that these are merely my wines of preference, not what I actually get

to drink. If you like something a little more assertive, basic Chianti

would work well with its savoury, herbal hints that come from the Sangiovese

grape. There’s no need to choose a white wine just because your pizza has a

few bits of chicken on the top. It’s the dominant flavours that count. But

if you are having a seafood or vegetarian pizza Sauvignon Blanc or a light,

dry rosé would be excellent choices.

The whole business of pairing pizza and

wine is pretty basic and boils down largely to whether you want the food and

wine to complement each other or whether like me, you prefer contrast. For

example, if you’re having a “heavy” pizza with lots of rich meat, you can

match like-with-like by selecting a full-bodied wine like a warm-climate

Cabernet Sauvignon or Shiraz. Alternatively, you can contrast your “heavy”

pizza with a light-bodied wine. It’s entirely up to you. Feel free to be

adventurous and try to experiment. Perhaps in these challenging times, you

might even finish up, as I so often do, with Mont Clair. But that’s better

than nothing, and with a bit of determination and will-power you can almost

convince yourself that it’s actually Valpolicella from sunny Italy.

|

|

Classic Reds

Château

Margaux (Photo: Colin Burbidge).

If you mention the name

“Bordeaux” to wine lovers, don’t be surprised if their eyes glaze over and

their salivary glands get to work like those of Pavlov’s slobbering dogs.

Because you see, for wine enthusiasts Bordeaux is rather special. Any red

wine from the Bordeaux region used to be called “claret” in Britain,

regardless of its origin or pedigree. The British have used this word for

the last three hundred years yet today it’s unknown in France. It’s always

pronounced “cla-rett” and never, as some nitwit once told me, “cla-ray”.

I suppose the word will eventually join the mausoleum of other defunct but

delightful English words along with hobgoblin, postilion, whirligig and

quagswagging, which in case you’re wondering, means shaking something to and

fro. My parents always used to speak of “listening to the wireless” and

avoided the word “radio” as though it was slightly vulgar. Future

generations will probably regard anyone who talks about “the wireless” as

faintly dotty if not actually barking mad.

So what can I tell you about Bordeaux

that you don’t already know? Well, Bordeaux is in France. Of course, you

knew that. Even my dogs know that. I suppose Pavlov’s dogs knew that too.

Furthermore, Bordeaux is almost half way between the North Pole and the

Equator. To be more precise, it’s two-thirds of the way down France’s

Atlantic coast and the city of Bordeaux lies on the 44th parallel

along with Minneapolis and Montreal.

The Atlantic Ocean and the rivers

Gironde and Dordogne, together with the warming effect of the Gulf Stream

have a significant impact the climate of Bordeaux. The name itself is a

contraction of the French expression au bord de l’eau which

translates roughly as “next to the waters”. They’ve been making wine there

since the 8th century

and today this region of 400 square miles is home to ten thousand wine

producers. Bordeaux wine is available at all levels of quality and price.

The prices of top quality Bordeaux wine vary from year to year depending on

the weather and therefore the quality of the vintage. For example, the years

1961, 1982, 1990, 2000 and 2009 produced superb wine while the 1991 and 1992

vintages were a complete washout.

We can’t talk about Bordeaux wine

without mentioning the so-called 1855 Classification. It was created at the

request of Napoleon III (the eponymous nephew of the famous one) who wanted

to showcase Bordeaux wine at the 1855 Paris World Exhibition. Local experts

ranked what they considered the Top Sixty reds of the Gironde region of

Bordeaux in order of importance from first growths (or cru) to fifth

growths. Surprisingly, the classification still holds today with only a few

minor changes. Every wine professional knows this list of Grands Crus

by heart. The five chateau named among the First Growths (Premiers Crus)

include such illustrious names as Château Lafite Rothschild, Château Latour

and Château Margaux which together produce some of the finest red wines in

the world. When aged, they develop into sensational wines, each with its

unique character.

They don’t come cheap. For example, the

UK price of a bottle of the year 2000 Ch. Latour is the equivalent of 39,000

baht and a bottle of Ch. Mouton Rothschild of the same year will set you

back 88,000 baht. You can double these prices for Thailand. But because of

the enormous world-wide demand, you would be hard-pressed to find any

grand cru wines in this country except at the most exclusive places.

However, you don’t need to sell the

family car (or the family) to buy a bottle of Bordeaux. The annual output

is about 900 million bottles and apart from that tiny minority of grand

cru wines, many of them are entry-level wines intended for everyday

drinking and labeled either Bordeaux AOC (Appellation d’origine contrôlée)

or Bordeaux Supérieur. The Bordeaux locals drink little else. You can easily

find this style of wine in Thailand and the online companies Wine-Now.Asia

and Wine Connection stock a decent selection of everyday Bordeaux

starting at under Bt 1,000.

If you’ve never tasted Bordeaux, you

might be wondering what to expect. Well, the signature grapes of Bordeaux

are always Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot. Many winemakers use a blend of

these two grapes and nothing else. Sometimes other grapes are added to

improve the blend, notably Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot and Malbec. Good

ordinary Bordeaux tends to be dry and firm-bodied with aromas of plum and

blackcurrant. It’s restrained in style and is usually high in tannins giving

it a firm structure. Sometimes there are touches of spice and hints of soft

fruit but these are always subtle and the polar opposite to some of the

Cabernet Sauvignon fruit bombs from Australia.

Many entry-level Bordeaux wines are

labeled Château something-or-other giving the impression of a stately

home surrounded by immaculate gardens and vineyards. This is merely a

marketing ploy. A wine company can legally sell identical wines under

different and totally fictitious châteaux names. It’s estimated that there

are ten thousand château names in use today. The wine in a bottle of cheap

Bordeaux may be perfectly good, but the picturesque château shown on the

label probably doesn’t exist.

|

|

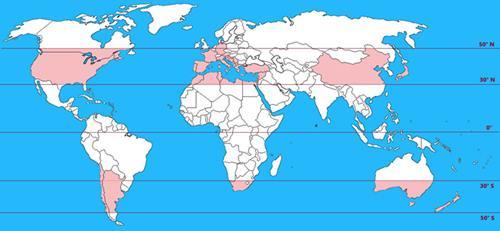

Changing Latitudes

Map showing 30°-50° latitudes.

If you wander through the wine section

of a typical supermarket you might get the impression that wine comes from

all over the world. But you’d be wrong. The bulk of the world’s wine

originates from grapes grown between 30 and 50 degrees of latitude in both

the Northern and Southern hemispheres. The Northern Hemisphere is by far the

larger wine producer because this band covers much more land, whereas the

Southern 30-50 degree band is mostly over oceans.

But perhaps you have forgotten what

“latitude” means, especially if your geography is a bit hazy. So let me

explain. On a map or globe of the Earth, latitude is shown by imaginary

horizontal lines like hula hoops around the surface from the equator to the

two poles. On a map, like the one shown here, they appear as straight lines.

They’re sometimes called “parallels” because they run parallel to the

equator which is the starting point for measuring latitude so it’s

considered as zero degrees. Thailand is comparatively near the equator and

Pattaya lies 12° North. One degree of latitude is around 69 miles (or 110

kms) so Chiang Mai is almost 19° N. London is about 51.5° N whereas on the

opposite side of the world, Sydney is about 35° South (usually shown as

-35°). This of course is within the southern grape-growing comfort zone.

The vertical lines on a map or globe

indicate longitude and knowing both these values you can pin-point anywhere

on the globe. This is partly how your GPS device works. Surprisingly

perhaps, the concepts of latitude and longitude have been known since